Meet the new wave of wearables: stretchable electronics

Scientists have figured out how to make electronics as pliable as a temporary tattoo—meaning the next big tech platform may be your skin.

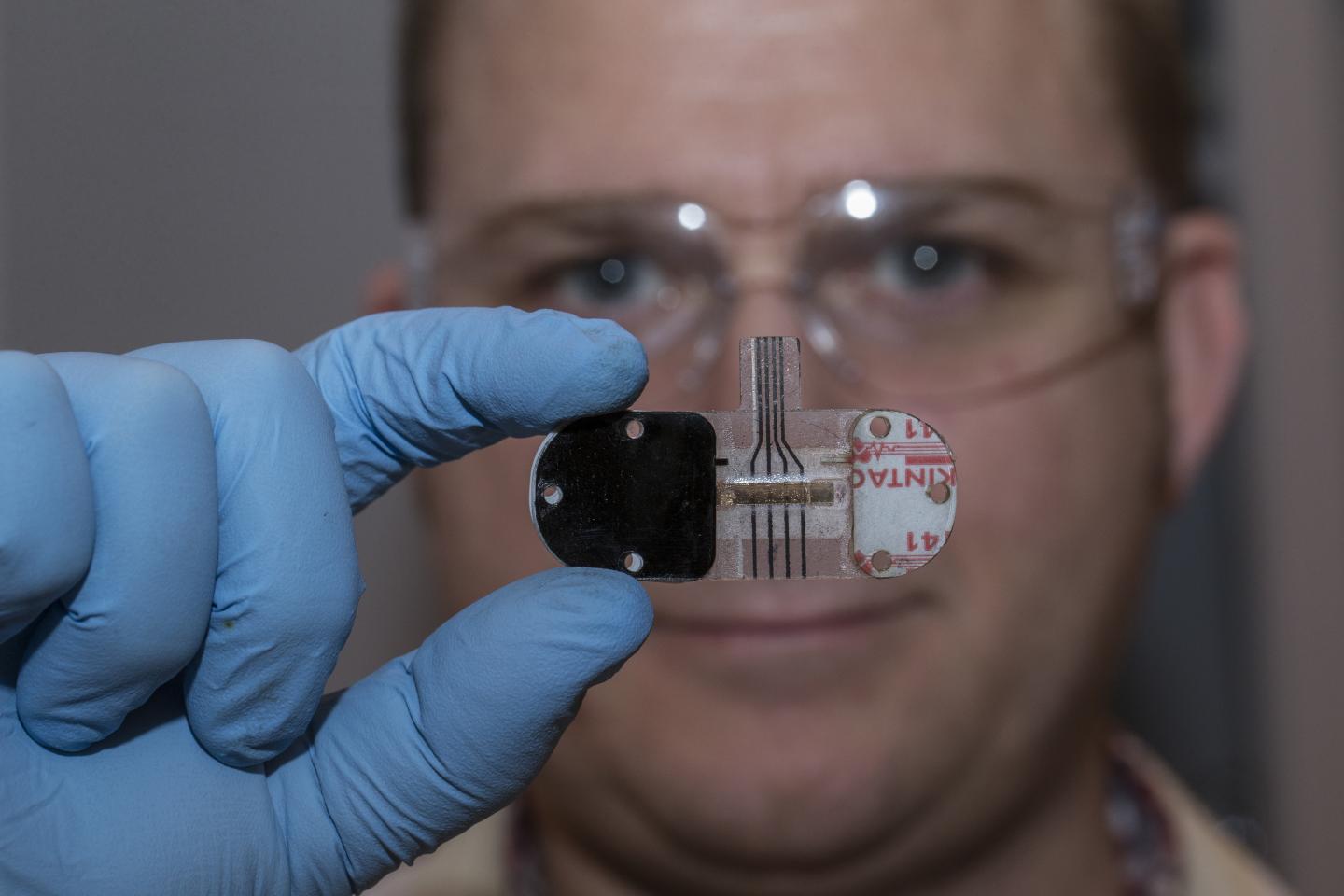

Second skin: Patches that measure electrical activity in the heart, brain and muscles — such as this device, from the Rogers Research Group at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana — could replace conventional medical hardware. Lauren Pisano photo.

Kim Lightbody, Fast Company June 20, 2016

If you purchase La Roche-Posay sunscreen this summer, it may come with a complimentary device that looks something like a heart-shaped Band-Aid. But it’s even thinner—half the width of a human hair—and unlike a Band-Aid, it contains miniature electronics that connect to your smartphone and monitor your sun exposure in real time.

Launching in June from La Roche-Posay parent company L’Oréal, My UV Patch is the first stretchable electronics for mainstream consumers. Stick it anywhere on your skin, wear it for up to five days, and use the accompanying app to see how many rays you’ve soaked up. If it sounds simple, it isn’t: the tiny device contains a near-field communication (NFC) antenna and a microchip, which wirelessly send signals to your phone, as well as photosensitive dyes that change color based on their exposure to light.

The product is the result of years of academic research into how to transform typically hard, rigid electronics into pliable materials that can easily conform to the contours of another object (particularly the human body) and send data to computers or smartphones using NFC and Bluetooth. With the technology finally advancing to the point of commercialization, stretchable electronics may soon impact everything from medical research to mobile payments to the way you navigate a crowded amusement park.

None of this was possible until 2006, when John Rogers, the head of the Rogers Research Group at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, published a paper with three of his colleagues explaining how they had developed a stretchable form of silicon by cutting and patterning the material into waves, allowing it to expand or compress like an accordion.

It was a revelation: silicon, the most widely used semiconductor in electronics, is naturally hard and brittle. That’s fine if you’re building a smartwatch, but it doesn’t lend itself to creating ultra-malleable devices that feel more like a second skin. Rogers’s achievement has sparked a flurry of activity in other university labs as engineers and scientists try to further his work and develop uses for it. “This is where wearables are likely to go next,” says Rogers. “A lot of people see this as the future.”

Rogers’ method of creating stretchable electronics isn’t the only one—some scientists are working with liquid metals rather than silicon, and others are focused on altering the molecular structure of organic materials to make them inherently stretchable—but for now, it’s the most ready for commercialization.

Rogers, who is moving his lab to Northwestern University in September, cofounded a company called MC10, a Massachusetts-based startup dedicated to bringing stretchable electronics to market. The company worked with L’Oréal on My UV Patch and has developed another device, the BioStamp Research Connect, which measures body motion, muscle activity, and heart rate. MC10 began selling the BioStamp to researchers and companies earlier this year. “It’s essentially a body-worn computer,” says Roozbeh Ghaffari, MC10 co-founder and chief technology officer.

Ghaffari’s team is also working with Rogers’s lab on studies at Chicago-area institutions, using the patches for physical rehabilitation and on neurosurgery patients. Rogers is overseeing a separate trial at the city’s Lurie Children’s Hospital, where the wireless, battery-free sensors replace cumbersome machines to monitor the vital signs of premature babies.

UC engineering student Adam Hauke holds up the latest generation of wearable sensor in UC’s Novel Devices Lab. Joseph Fuqua II, UC Creative Services

For the next generation of the technology, both MC10 and Rogers are exploring how stretchable electronics can collect and analyze bodily fluids, such as sweat. This would allow the devices to measure biomarkers like electrolyte levels in athletes or glucose levels in diabetics. Rogers is running one of these microfluidic studies with L’Oréal, which is interested in how the technology could monitor skin health. “Hydration is an important part of antiaging,” says Guive Balooch, global vice president of L’Oréal’s technology incubator, which produced the My UV Patch. “If you can measure different attributes of the sweat, you can start to understand the personalized beauty routines and skin health of consumers.” The U.S. Air Force has also shown interest, partnering with Rogers to test the device on its members, measuring things such as total sweat loss during exercise.

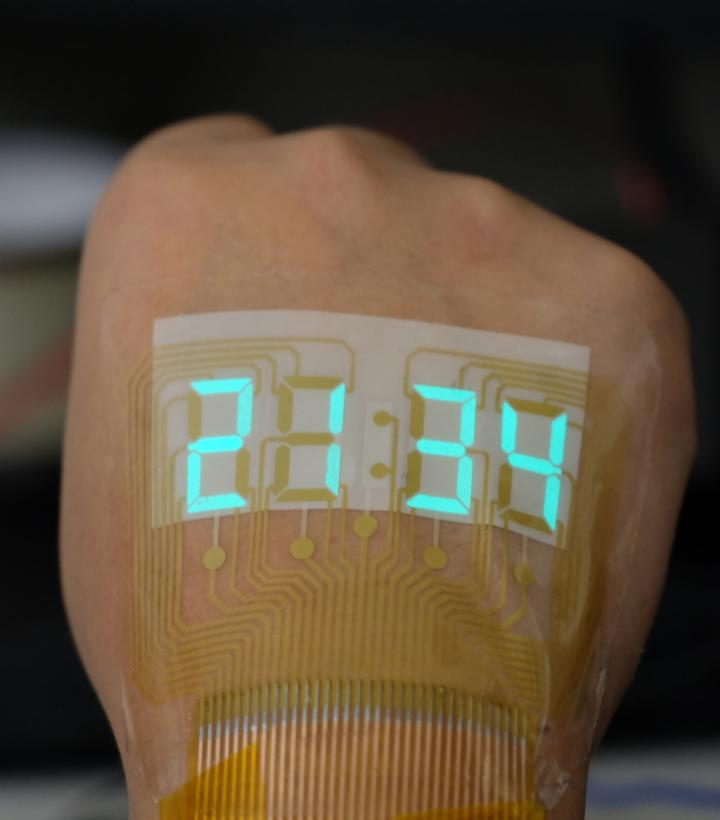

A stretchable light-emitting device becomes an epidermal stopwatch. ACS Materials Letters 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.9b00376

Additional consumer applications are on the way: MC10 is working on devices that could be used for cashless payment, interactive gaming, and live events—which Ghaffari says could be market-ready within a few years. Though MC10 isn’t sharing much information about its partners, stretchable electronics could enable users to pay for groceries or access a hotel room with the wave of a hand or participate in enhanced gaming experiences. Imagine a video-game console that monitors heart rate, temperature, and movements, and responds to them in real time with new challenges and environments.

“Electronics keep getting closer to us—from a computer on your desk to a Fitbit on your wrist,” Rogers says. “We’re just scratching the surface.”

Source Fast Company

A version of this article appeared in the July/August issue of Fast Company

| Flexible, Conductive, Pressure Sensing Electronic Skin |

The American Chemical Society is profiling the work of scientists at Stanford who are developing “electronic skin,” a material that’s both flexible and stretchy while sensing pressure and transmitting electric signals. It may end up being used for prosthetic hands to give amputees the sense of touch.

Here’s an ACS video with the scientists that show you how the material works:

| How to Make Electronic Skin with Stanford’s Zhenan Bao—Speaking of Chemistry Road Trip. Stanford’s Zhenan Bao and her research team are developing electronics that could revolutionize wearables and prosthetics. In this episode, Matt Davenport and Noel Waghorn get a glimpse behind the scenes at Stanford and learn how Zhenan’s past at the historic Bell Labs is helping her create futuristic materials. The Speaking of Chemistry California road trip continues as we scope out some cutting-edge, flexible electronics at Stanford University. Reactions. Youtube Jun 27, 2016 |

Source Medgadget June 28, 2016

| References |

Biaxially stretchable “wavy” silicon nanomembranes, Choi WM, Song J, Khang DY, Jiang H, Huang YY, Rogers JA. Nano Lett. 2007 Jun;7(6):1655-63. Epub 2007 May 8.

| Further reading |

Stretchable High-Permittivity Nanocomposites for Epidermal Alternating-Current Electroluminescent Displays, Yunlei Zhou, Chaoshan Zhao, Jiachen Wang, Yanzhen Li, Chenxin Li, Hangyu Zhu, Shuxuan Feng, Shitai Cao, and Desheng Kong, ACS Materials Lett. 2019, 1, XXX, 511-518. October 4, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.9b00376. PDF

Biomedical engineering, Electronic devices, Health care, Implants, Soft materials, Jaemin Kim, Roozbeh Ghaffari & Dae-Hyeong Kim. Nature Biomedical Engineering, Article number: 0049 (2017) doi:10.1038/s41551-017-0049

The quest for miniaturized soft bioelectronic devices, Kim J, Ghaffari R. & Kim D. Nat Biomed Eng 1, 0049 (2017) doi:10.1038/s41551-017-0049

Nanomaterials in Skin-Inspired Electronics: Toward Soft and Robust Skin-like Electronic Nanosystems, Son D, Bao Z. ACS Nano. 2018 Dec 26;12(12):11731-11739. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07738. Epub 2018 Nov 21. Review. Erratum in: ACS Nano. 2018 Dec 26;12(12):12943.

Skin-Inspired Electronics: An Emerging Paradigm, Wang S, Oh JY, Xu J, Tran H, Bao Z. Acc Chem Res. 2018 May 15;51(5):1033-1045. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00015. Epub 2018 Apr 25. Review.

Monolithic Solder-On Nanoporous Si-Cu Contacts for Stretchable Silicone Composite Sensors, Kasimatis M, Nunez-Bajo E, Grell M, Cotur Y, Barandun G, Kim JS, Güder F. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019 Dec 18;11(50):47577-47586. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b17076. Epub 2019 Dec 6.

Stretchable, Skin-Attachable Electronics with Integrated Energy Storage Devices for Biosignal Monitoring, Jeong YR, Lee G, Park H, Ha JS. Acc Chem Res. 2019 Jan 15;52(1):91-99. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00508. Epub 2018 Dec 26. Review.

Also see

MC10 Receives FDA 510(k) Clearance for the BioStamp nPoint™ System Business Wire

Stretchy and squeezy soft sensors one step closer thanks to new bonding method Imperial College London

Stretchable silicon could be next wave in electronics University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

MC10 teams with Shirley Ryan AbilityLab to tackle neurodegenerative disorders MobiHealthNews

UCB, MC10 complete Parkinson’s trial, plan to publish data in 2017 MobiHealthNews

MC10, researchers in Korea build prototype glucose management peel-and-stick patch MobiHealthNews

MC10, University of Rochester to test stretchable medical sensors, develop predictive health analytics MobiHealthNews

More on the first five Apple ResearchKit apps MobiHealthNews

A stretchable stopwatch lights up human skin American Chemical Society