New approaches to orthotic management in children with cerebral palsy

Practitioners look to novel ways of using familiar lower limb orthotic alternatives to complement new technology.

No single treatment is appropriate for every child, but it is generally agreed that the sooner intervention is started the better the outcome.

Dynamic ankle-foot orthosis, DAFO. Cascade DAFO

by Carey Cowles, Healio O&P News April 2013

| Goals of orthotic management |

Spastic cerebral palsy is the most common type of cerebral palsy, found among approximately 80% of children with the disability. Although orthotic intervention has adjusted in small ways to accommodate new research into body mechanics and gait, the overall goals are the same.

According to the International Society of Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO), the goals of lower limb orthotic management of cerebral palsy are to correct and/or prevent deformity; to provide a base of support; to facilitate training in skills; and to improve the efficiency of gait. Other goals include increasing range of motion, maintaining or improving levels of function and stability; maintaining muscle length as the bones grow, and preventing or overcoming some of the secondary effects of the disability leading into adulthood.

In the Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics, Christopher Morris MSc SR Orth, suggested that some degree of compromise between affecting body structure vs. overcoming activity limitations is necessary “because orthoses prescribed to prevent or correct deformities can impose additional activity limitations by restricting movement.” He suggested that “normal functional development can be impeded by impairments of coordination and movement. Orthoses can maintain optimum biomechanical alignment of body segments encased with the orthosis. These effects may enable children to overcome activity limitations by focusing training on unrestricted parts of their bodies over which they have better control.”

A multidisciplinary team including an orthotist, physical therapist and an orthopedist can advance a child with cerebral palsy along the continuum of care throughout his development. This team, coordinating with a family-centered approach to care, should encourage optimal use of an orthosis within the prescribed treatment plan.

There are different and evolving schools of thought regarding the use of orthotic intervention. Some practitioners believe less bracing is better and that positive development can come from muscle stretching, training and strengthening exercises. There is a trend toward making below-the-knee only orthoses and using flexible AFOs to maximize gait and performance. Now, treatment has found its way toward options such as electrical stimulation and the use of botulinum toxin A injections and the subsequent challenge of creating orthoses based on the muscle dynamics that result.

| Where to start |

Orthotists need to take time to consider real-world function and consider the effect of any orthosis on a child’s ambulatory skills, whether it is on the playground, in the park, the schoolyard or the backyard, said John Kooy, CO (c), Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Toronto. “We have to consider what’s happening in those settings vs. the clinical environment of a wide open, flat hallway. Does that necessitate a change in the orthotic prescription? I don’t think we know enough to say whether it does or not.”

It is important to remember that providing orthotic care to this patient population does not follow a one-size-fits-all approach. An orthosis must fit well, and control the ankle, forefoot and hindfoot. Total contact is important because of the deviations in planes of the foot. A loose brace may cause skin breakdown; an orthosis that is dorsiflexed may cause discomfort and decreased function in a child who doesn’t have adequate dorsiflexion range of motion.

According to Scott Amyx, CO, senior orthotist at the University of Wisconsin, Hospital and Clinics, Orthotics Lab, in Madison WI, getting a good skeletal alignment is the foundation to getting the muscles to operate more effectively. Patients with spasticity may have inherent body weakness that affects their inability to control their muscles. Strengthening those muscles, once thought to increase spasticity, is now a critical part of a multidisciplinary approach to treatment.

“It’s crucial you get decent alignment. By controlling the alignment we’re going to have a bigger impact on the spasticity,” Amyx told O&P Business News.

“Years ago the common wisdom was to put all these bumps and grooves into the footplate and that’s going to reduce spasticity by the neurosensory input. That’s been pretty much proven that it really doesn’t. If that were the case we’d be able to put a foot orthosis in a shoe and they would have a reduction in spasticity. That didn’t happen. We still have to use AFOs.”

Amyx said a neutral alignment reduces the power of over-powerful muscles, and gives underused and underpowered muscles a chance to increase in strength and be more effective.

“If you stretch a muscle too far it loses a lot of its strength and effectiveness. If you have a kid who’s really pronated, all the medial muscles are overstretched and the lateral muscles are pulling on the foot. If we can get them into neutral heel alignment and get the forefoot in the right position, that would help reduce spasticity more because of the skeletal alignment rather any sort of bumps or grooves we’re putting in the bottom of the footplate.”

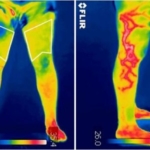

Elaine Owen, MSc SRP, MCSP, superintendent and clinical specialist physiotherapist at the Child Development Centre in Bangor, UK, told O&P Business News that segment kinematics are just as important as joint kinematics when considering AFOs. Owen presents a course on shank and thigh kinematics at the Rehabilitation Institute in Chicago.

“If you see segments and joints as completely independent, you can get some perspective. When the foot and the shank kinematics are correct, you can more easily correct the thigh, pelvis and trunk kinematics and kinetics.”

She stressed that in addition to the angle of the ankle — in an AFO, the shank relative to the foot — the shank to vertical angle of an AFO footwear combination (AFOFC) is equally important in building a foundation for orthotic intervention.

“The reason for that is because small adjustments to the shank to vertical angle can make big changes in gait, particularly in children with neurological conditions.”

| AFO options |

According to a consensus report from the ISPO, AFOs that control the foot in stance and swing phase can improve gait efficiency in children with cerebral palsy (GMFCS levels I-III). The report suggested little evidence supporting the use of orthoses for the hip, spine or upper limb.

The trend toward using less rigid materials to craft AFOs allows the child more motion, according to Amyx.

“One of the products we just started exploring is the Ultraflex Safestep. It’s got polyurethane “bumpers” and stops so we can modulate planterflexion and dorsiflexiojn to give kids more motion than we have in the past, but we can slow down some of the extraneous motion we don’t want. That looks really promising,” he said.

Owen advocates the use of an AFOFC. “With AFOs, the footwear hasn’t been recognized as being as important as it really is. The footwear is as important as the orthosis.” She said it is acceptable to allow plantarflexion angles of the ankle in the AFO when required.

“Traditionally there has been a lot of use of 90· angle of the ankle in the AFO, when that might not always be the optimal alignment of the foot relative to the shank. That may change the bony alignment of the foot, and the child may not be extending their knee fully in gait. They might walk with a flexed knee gait and therefore not be stretching their calf muscles.”

Owen disagrees with the notion that the foot has to always be supported at 90·and that by failing to do so, the child cannot get good knee extension in gait.

“If you come from a belief that you can put the ankle at any position and it’s the shank to vertical angle and the alignment of the AFO footwear combination that will give you the knee extension, then you can get away from always using the 90· ankle angle. It’s the shank to vertical angle that will determine gait as opposed to the angle of the ankle in the AFO, as long as that is optimal. Then we can choose any ankle angle that is appropriate and we can design AFOFCs optimally for each leg of each child.”

Footwear designs can change the effectiveness of the orthosis.

“Determine the optimal angle of the ankle in the AFO, determine the optimal shank to vertical angle of the AFOFC and then determine the optimal heel and sole design of the footwear,” Owen said.

Based on an algorithm for designing and tuning AFOFCs, it is best to tune the alignment, then tune the heel design for entrance into mid-stance, then adjust the sole design for exits from mid-stance. For some abnormal gaits, she recommended a point loading rocker position adjusted for pathology.

| Functional electrical stimulation |

A recent study conducted by the National Institutes of Health was the first to investigate the use of the WalkAide for the treatment of dropfoot in children with cerebral palsy. The goals of the study were to compare efficacy vs. an AFO and overall compliance.

Twenty children in the study wore the WalkAide 6 hours a day for 6 months. The children wore the device during daily activities; once they were settled in for the night, they did not wear orthoses.

Gregg Beideman, DPT, a rehabilitation specialist with Innovative Neurotronics, the device manufacturer, fit the device on the children in the study. He told O&P Business News that 95% of the children continued with the device after the study ended.

“There was great compliance,” he said. “There’s been a hesitation to use it because you’re afraid whether they’ll continue to use it. They not only continued to use it but they preferred it. All of the kids in the study had an AFO made for them at some point in thier lives, but only a handful of them were still wearing them regularly and some refused to wear them altogether. Compared with an AFO over time, they continued to show improvement. The more they wore the device the better clearance they had during swing over time.”

The device triggers an electrical impulse into the peroneal nerve that signals the muscles that pick up the toes during gait. It also tries to reconnect the neural signal from the foot to the brain that is impaired with children with cerebral palsy.

“Over time, that can restore that ability to pick their toes up even when they’re not wearing the device, something an AFO can’t do,” Beideman said. “We’re seeing serious improvement in that connection but we need more research to formalize that that can happen. This is the first study in kids.”

The device, previously limited to adults because of the cuff size, now has a cuff that fits children as young as 3 years old. In the past, orthotists had to make custom cuffs to fit the device to children.

“We’ve been able to change the waveforms so smaller legs can tolerate the electricity,” Beideman said. “It was something that physicians didn’t previously recommend because they didn’t know the settings could be modified for children. However, now, it’s become a little more mainstream for the physician to recommend the Walk Aide and an orthotist to deliver it.”

Beideman said children tend to have better outcomes than adults because treatment can positively affect gait patterns before they become habit. Amyx has seen some positive results with the WalkAide, but said parents may shy away from using it because it is not typically covered by insurance.

While the most important results of the study that will impact children with cerebral palsy are set to be published sometime this year, Beideman thinks there will be more advances in functional electrical stimulation so the technology can be more readily used for other parts of the body. “This is going to help kids with cerebral palsy with their upper extremity and hip flexors. You’ll see that trend in the next 5 years,” he predicted.

But for now, the technology can be combined with orthotic management and perhaps down the road, actually built into an orthosis. “FES isn’t always the only solution; while it predominantly does well by itself, there might be a hybrid that can transition from a bracing solution to an FES solution or a combination thereof,” he said. Between the therapy and the orthosis, “a nice working relationship allows you to do that, instead of just one or the other.”

| Pharmacological and alternative intervention |

Dynamic orthoses can complement other treatments, including botulinum toxin therapy and post surgical recovery. At the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, clinical and orthotic management of children with cerebral palsy has included the use of botulinum toxin A for more than a decade.

According to Darcy Fehlings MD MSc FRCPC, associate professor of Paediatrics, University of Toronto and senior scientist at the Bloorview Research Institute, there are three main indications for the use of botulinum toxin A in a child with hypertonia: a potential to improve motor function, ease of caregiving, and painful muscle spasms.

“Botulinum toxin can be quite effective. We have evidence that it shows improvement in equinus management and gait functioning in children who are ambulatory with cerebral palsy in the short term. Most of the trial evidence is for 6 months. After that, the child comes back in to be reassessed for a repeat reinjection.

“Under 7 years of age, we might consider botulinum toxin injection every 6 to 9 months. As the children get older the indications tend to narrow a bit to improve gait and motor function. After this age we are often injecting less frequently,” she told O&P Business News.

Fehlings said her team often uses botulinum toxin A in conjunction with serial casting to help improve range of motion or flexibility, particularly in the gastrocnemius muscle. Serial casting can cause weakness in the muscle, which may require more stability in the orthosis. Increased stability allows for improved function as the child improves his range of motion as a result of therapy after receiving botulinum toxin.

They follow that with a hinged AFO for up to 6 hours daily to help stretch the muscle while the child is walking. Fehlings and her team also perform a modified Tardieu evaluation to assess where the child first develops hypertonia in a passive stretch.

“We look at that angle. Then we keep stretching the muscle to see what the passive flexibility is of the muscle. The largest distance between the first catch and the second catch…that’s the dynamic range that the botox will be effective in. So as long as that range is significant, and that depends on the joint, then botulinum toxin can be effective.”

An orthotist who encounters a child with cerebral palsy who has undergone botulinum toxin treatment needs to consider the level of function and the goals of the patient and family.

| Recommendations for using lower limb orthoses in children with CP |

The following conclusions and recommendations for the use of lower limb orthoses resulted from an evaluation and subsequent discussion of the review papers presented at a 2008 meeting of the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics ISPO.

| Lower limb orthoses |

- For ambulant children, the available evidence from gait laboratory studies suggests that ankle foot orthoses (AFOs) that prevent plantarflexion can improve gait efficiency improving temporal and spatial parameters of gait, (ie, velocity, cadence, step length, stride length, single and double support) and ankle kinematics.

- The indirect effects of AFOs on the kinetics and kinematics of the knee and hip joints have been demonstrated in gait laboratory studies; and these effects can be optimized by tuning the orthoses.

- The energy cost of walking may be decreased by the use of AFOs.

- It is unclear whether and how AFOs influence phasic activity of lower limb muscles.

- It is unclear how the assessment of the efficacy of AFOs in the gait laboratory can be used to predict children’s mobility and gait efficiency in their usual environments.

- There is inconclusive evidence of the effect of AFOs on children’s motor function. The Gross Motor Function Measure has been shown to be sensitive to the changes associated with use of orthoses and mobility aids and could be used to evaluate this outcome.

- It unclear whether AFOs can maintain/increases muscle length and hence prevent/reduce deformity developing over time.

- Long-term effects of orthoses on muscle strength are unknown. Given recent recognition of the importance of muscle strength and endurance for maintaining mobility into adulthood, further research on this topic is desirable.

“We want to consider functions such as going from floor to standing, which may call for a little more ease of mobility around the ankle. With stair transitions, we try to keep them in a hinged AFO during that time,” Kooy said. “As they start to get older, levers become longer, weight gets greater, and when evaluating their overall strength and range of motion, do we need to consider hinging the AFOs with limitations, or should we consider more of a rigid style AFO?”

Kooy said in higher classes of the GMFCS levels, at level III, the aim is to reduce the tendency to crouch, but that comes with risks. “Is it a better option to stay with a rigid AFO vs. allowing them some more movement at the ankle perhaps resulting in increased crouching — which would decrease function and increase energy expenditure in gait?”

“With botox, because they have more flexibility, we can get them into a 90· AFO easier than before botox,” Amyx said. “With dorsal rhizotomy, we have to go to a more solid ankle AFO initially with dummy hinges and hopefully we can articulate it later. Most kids are stereotypically very weak after the rhizotomy is done. They can’t use an articulated AFO or they might sink into crouch.”

| Novel approaches |

Amyx approaches supramalleolar orthoses differently than most by articulating them.

“We do that because an SMO primarily controls medial-lateral instability of the foot. And so if you have a standard SMO, as they advance their tibia over the foot, it’s coming out of those supra malleolar “wings” at the terminal stance, so they’re able to pronate inside the brace. We decided to articulate them so when they come forward we’re still able to use the tibia to try control the foot and so as they advance their tibia they’re getting a ground reaction force that’s pushing against the tibia to help control the foot. Typically when we do those, they’re free-motion, full plantarflexion and dorsiflexion; we’re concerned with the pes planovalgus,” he said.

New technology and advances in gait mechanics have evolved so that practitioners are using orthoses and biomechanics to access the nervous system, Owen said. “That requires a lot of perfect practice. Children with disability find it hard to learn by trial and error. They often have to have errorless learning. They need to get it right to learn it, and using orthoses so they can get it right to learn it is a new way to use orthoses. We’ve always used orthoses to help bony alignment and perhaps stretch muscles. Accessing the nervous system is a really important way of using them, particularly with neurological conditions, and children who are learning to walk with them,” she said.

As part of a hospital based multidisciplinary team, Amyx acknowledged he has access to treatments that some private practices may not offer. “Typically not found in a private practice, we have the GAITrite, a mat that with sensors that records temporospatial data, and a gait lab,” he said. The multidisciplinary team at the University of Wisconsin comprises rehabilitation professionals, occupational and physical therapists and an orthopedic surgeon. Holland Bloorview also focuses on multidisciplinary treatment and family centered care.

Kooy acknowledged that there is nothing drastically different in orthotic treatment but there is now more careful examination of the literature. “People are trying different ideas. It still depends a lot on evaluation,” he said.

Owen concurred, and said moving forward, a critical goal of using orthoses for children with cerebral palsy or other pathologies is “finding ways to make these things work better than they used to.”

Source Healio

| References |

Recent developments in healthcare for cerebral palsy: implications and opportunities for orthotics, Morris C, Condie D. International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics, Oxford UK. Sept. 8-11, 2008

Muscle plasticity and ankle control after repetitive use of a functional electrical stimulation device for foot drop in cerebral palsy, Damiano DL, Prosser LA, Curatalo LA, Alter KE. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013 Mar-Apr;27(3):200-7. doi: 10.1177/1545968312461716. Epub 2012 Oct 4.

Long-term therapeutic and orthotic effects of a foot drop stimulator on walking performance in progressive and nonprogressive neurological disorders, Stein RB, Everaert DG, Thompson AK, Chong SL, Whittaker M, Robertson J, Kuether G. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010 Feb;24(2):152-67. doi: 10.1177/1545968309347681. Epub 2009 Oct 21.

A multicenter trial of a footdrop stimulator controlled by a tilt sensor, Stein RB, Chong S, Everaert DG, Rolf R, Thompson AK, Whittaker M, Robertson J, Fung J, Preuss R, Momose K, Ihashi K. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2006 Sep;20(3):371-9.

Comparison of 2 Orthotic Approaches in Children With Cerebral Palsy, Wren TA, Dryden JW, Mueske NM, Dennis SW, Healy BS, Rethlefsen SA. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015 Fall;27(3):218-26. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0000000000000153. PDF

Efficacy of ankle foot orthoses types on walking in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review, Aboutorabi A, Arazpour M, Ahmadi Bani M, Saeedi H, Head JS. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2017 Nov;60(6):393-402. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2017.05.004. Epub 2017 Jul 13. Review.

PR0221-GB_CP-Handbuch_Englisch

A Concept for the Orthotic Treatment of Gait Problems in Cerebral Palsy, FIOR & GENTZ, 5th Edition

Also see

NIH study shows WalkAide improves walking ability in children with CP The O&P EDGE

The New Generation of AFOs The O&P EDGE