Why doctors hate electronic records — and what could change that

The health care industrial complex has spent billions of dollars and untold amounts of time trying to make medical records as flexible, invisible and unobtrusive as possible for patients and clinicians alike.

Dr. R. Adams Dudley, who has an administrative IT advisory role at UCSF, talks about over-the-counter drugs with patient Helene Lynch, 80, from San Francisco as they search on the internet on May 24, 2017. Liz Hafalia, The Chronicle

By Dominic Fracassa, San Francisco Chronicle June 12, 2017

The results will be well worth the expense, the thinking goes, if the records — tracking patients in the vast and complicated health care system — could help clinicians spend more time caring for people and less on paperwork.

But after nearly two decades of concerted innovation, amid a push to do away with paper records, many physicians say they’re still hamstrung by issues that have dogged them for years. We’ve replaced the medical chart with a patchwork of systems that impose on doctors’ precious time and have yet to deliver clear improvements.

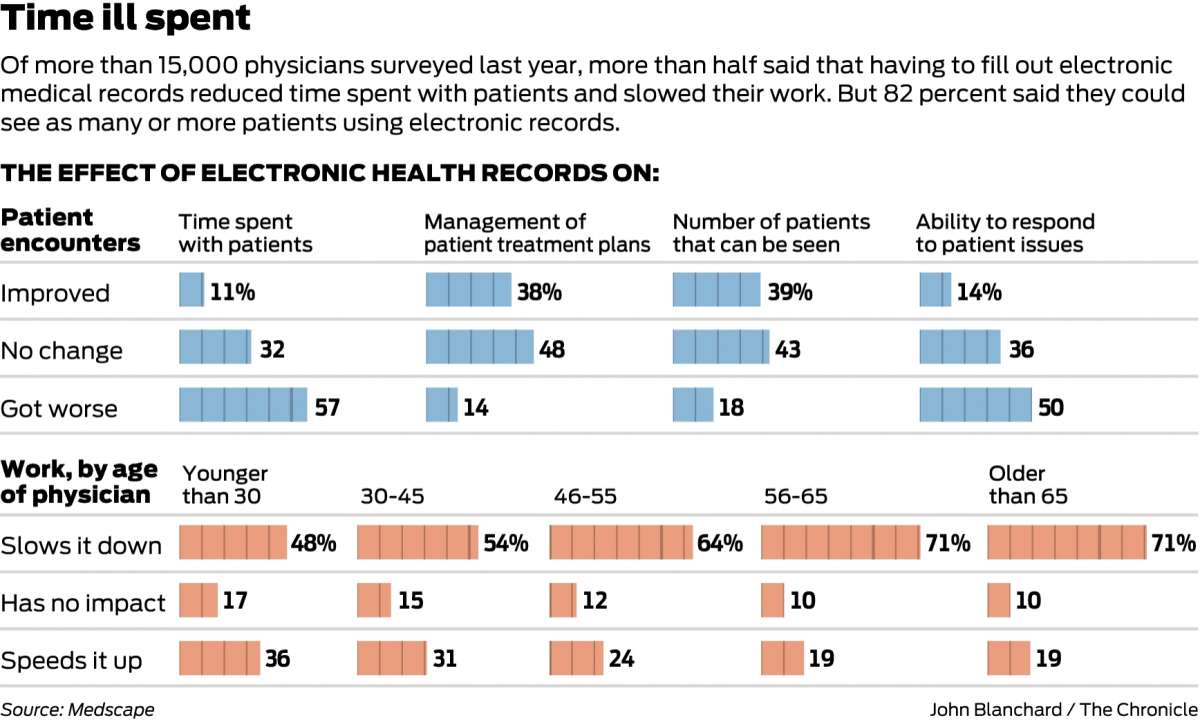

In a report last year by Medscape, a trade publication, 57 percent of more than 15,000 physicians surveyed said that having to grapple with electronic records was reducing the amount of face-to-face time they were able to spend with patients.

“We’re not at the promised land,” said Dr. R. Adams Dudley, a pulmonologist and the director of the Center for HealthCare Value at UCSF.

Change may be coming. Beyond improving documentation for doctors, large health systems are taking advantage of the troves of patient data to make better decisions in critical situations.

For hospital patients, Kaiser Permanente of Oakland has developed an algorithm that factors in a combination of vital-sign monitoring with data pulled from electronic medical records to predict the risk of rapid deterioration.

If the algorithm deems a patient to be at risk, hospital staffers are sent an alert.

“If we can identify some, many or all of those patients before they experience that (negative) event, and can help avoid that event, then the view is one can reduce complications and reduce morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Pat Conolly, a Kaiser executive who oversees information technology efforts. The early alert system, she said, will be implemented across all Kaiser hospitals.

At UCSF, Dudley’s team is developing a similar predictive modeling program that will be used to determine if a patient needs to be put on a breathing machine, as well as the patient’s probability for surviving in an intensive care unit. That matters, he said, because families must decide how much they want their loved ones to endure.

“I do think we’re still learning about all the stuff we can use” from electronic medical records, he said. “There are tremendous advantages to getting the information in electronic form, but it isn’t happening overnight.”

|

According to Medscape’s survey, 96 percent of physicians said they currently use or plan to implement an electronic medical record system. Despite the shortcomings, most agree that electronic records continue to improve, giving hope that eventually, filling out a patient’s chart will be as seamless as checking their reflexes.

In recent years, companies from small startups to large health systems have stepped in to try to make electronic records more data-rich, easy-to-use and more adaptable than ever before.

“A big part of our goal is to encourage the technology to be as invisible as possible,” said Matthew Douglass, a co-founder and senior vice president of customer experience at Practice Fusion, a San Francisco electronic medical records company whose software is used in 32,000 medical practices nationwide.

Douglass said Practice Fusion routinely tests experimental features with small groups of volunteers, and allows any customer to submit ideas for improvements.

“It can be anything from improving the way we handle data entry to making it so (the doctors) aren’t typing so much, all the way through rolling out more advanced ways of prescribing medication, so medicine ends up at the pharmacy when it’s ready” for patients, he said.

Pelu Tran, the president and co-founder of Augmedix, an electronic medical record startup in San Francisco, said that for years, innovation in electronic medical records was focused on making billing more efficient.

Companies made impressive strides toward that end, but at the expense of largely ignoring improvements to features that could contribute to better patient care.

“All the effort has gone into making sure you can find the billing stuff. The clinical stuff has gotten far less attention,” said Dudley of UCSF.

Augmedix’s solution is to give physicians a “hands-free” way to fill out their patients’ records without having to break away to enter information on a laptop to tablet.

Equipped with a Google Glass headset, doctors are able to interact with their patients while a trained medical scribe, linked to the doctor by audio and video, takes notes and fills out the pertinent paperwork. The physician can quickly review the notes and approve them after the patient departs.

“The complaint doctors and patients have is they feel rushed and that they’re not getting enough attention,” Tran said. “These issues are all tied to… documentation. Doctors are too busy and margins are too thin for them to spend the time making sure the paperwork has i’s dotted and t’s crossed.”

Dr. Nikola Lozano, a family practitioner in Petaluma, said that electronic medical records are indeed a hassle. “You spend more time with your (electronic medical records) than you spend taking care of people, which is sort of the original purpose of them.

“For me, in an ideal world I wouldn’t deal with an electronic medical record at all.”

Source San Francisco Chronicle

Source San Francisco Chronicle

| Further reading |

It is like texting at the dinner table’: a qualitative analysis of the impact of electronic health records on patient–physician interaction in hospitals, Kimberly D Pelland, Rosa R Baier, Rebekah L Gardner. Journal of Innov in Health Inform. 2017; 24(2)216-223. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/jhi.v24i2.894

Also see

Residents Spend More Time on Computer Than With Patients Medscape

Hospital, office physicians have differing laments about electronic records Brown University

Beating Burnout: Are EHRs the Enemy? Commentary Medscape

EHR Workarounds: Work Smarter, Not Harder Medscape

The EHR Feature Doctors Hate Most Medscape

EHRs, Clerical Tasks Contribute to Physician Burnout Medscape

Is Technology To Blame For Physician Burnout? Health IT Outcomes

Medicine 3.0: The Complex Role of Technology in a Doctor’s Life Medscape