Where are powered wheelchairs going?

It’s a valid question, and the answer is an optimistic one. But to get to the answer, we have to understand the past, present and future of power chairs.

B500 Power Wheelchair. Otto Bock

By Mark E. Smith, New Mobility April 1, 2017

The most common question I hear regarding innovation in mobility products relates to power chairs, and it’s not a positive one: Why are power chairs so behind the times when it comes to technology? After all, considering the advent of smart phones (computers in our pockets) and self-parking cars, why don’t power chairs use more advanced technologies?

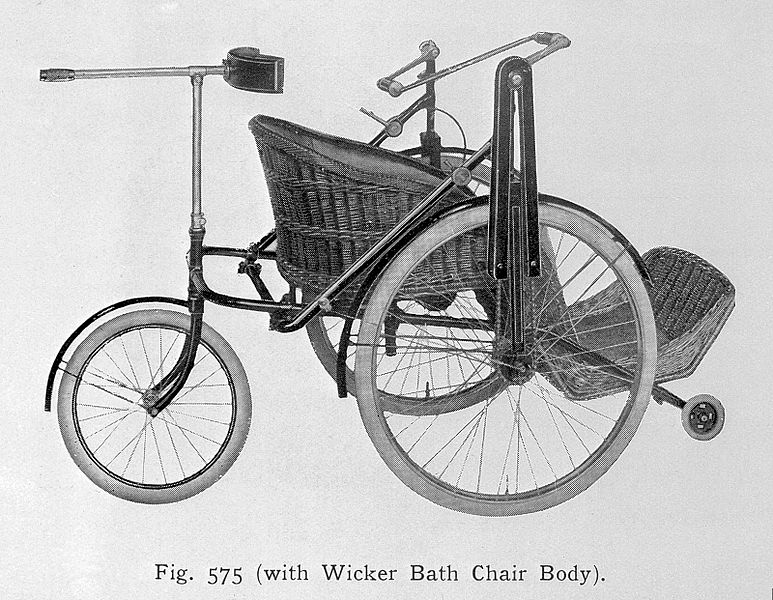

Devised by James Heath of Bath, England about 1750, the Bath chair was ‘intended for use by ladies and invalids,’ often incorporating glass wind screens and retractable canopies for comfort. Later versions were a type of wheelchair pushed by an attendant rather than pulled by an animal. The Bath chair was especially popular during Victorian times, when it was used at seaside resorts. This hand-pedalled Rotary Invalid Tricycle is from an R.A. Harding trade brochure published in London, 1920s. Wellcome Library, London

| A Brief History of the Power Chair |

The concept of the power chair goes back more than 100 years, to 1912, when a combustion engine was added to a cart-like device called the “Invalid Tricycle.” Following its quick failure, George Westinghouse, a driving force in modernized electricity, produced drawings around the same era for an “electric wheelchair,” but he was unable to bring his vision to fruition before his death in 1914. In 1916, the first commercial power chair was produced, but its high cost prevented any practical success.

The concept of the power chair all but disappeared until 1953, when Canadian researcher George Klein assembled a team to motorize folding manual wheelchairs for WWII veterans. By 1954, Klein had a reliable system that used a controller, batteries, a hand control and two motors — the concept that runs power chairs today. While Klein’s design was a ground-breaking success, it was Everest & Jennings that copied the system, launching its U.S. model, the 840, in 1956.

During the 1970s, power chairs were fragile, with limited capabilities, regarded by manufacturers and society as an institutional device. Although power chairs slowly progressed over the years, there were no huge leaps in innovation until the 1980s. At that time, however, the independent living movement demanded more, and that’s when steady innovation truly began. Still, it wasn’t until about 2000 when major advancements culminated, and the power chair became a tremendous tool of independence, with power seating, high-speed motors, extended battery range and suspension as common features.

By 2006, though, major funding and coding changes dramatically slowed access to power chairs by consumers and innovation by manufacturers. Funding cuts reduced coverage across the board and eliminated many advanced technologies altogether. The tragedy of this was that many other technology sectors were booming with breakthroughs that could have benefitted power chairs — from battery innovations to advanced electronics — but the funding cuts curbed most of them. It would be 2010 before funding had stabilized enough to regain steady innovation.

Fortunately, for consumer protection, power chairs have been placed under increasingly stringent regulatory processes over the years. They are now considered an FDA Class-II Medical Device. This regulatory process affects all aspects of a power chair, from concept to manufacturing. Along the process, aspects like safety and durability are tested and proven — and it all takes time. Based on the complexity and regulatory success of a component or power chair product, it can take two to five years to move from concept to finalization, causing a sometimes unavoidable lag in feeding mainstream technologies into the FDA-regulated power chair market.

An Entirely New Angle. Permobil

| Finally, Technology is Catching Up |

The good news is after years of slow progress, the power chair industry is back on track when it comes to innovation. Since 2015, we’ve seen major manufacturers introduce advanced technologies that are truly changing lives. Permobil has made gyroscope tracking technology standard on its F- and M-Series models for improved drive control. Quantum has its iLevel system that mechanically stabilizes the power base when the seat is elevated, allowing walking speed and height over varied terrain. And, Quickie’s SEDEO Ergo seating uses biometrics for advanced power positioning. Across the board, we also see Bluetooth integration for controlling electronic devices; ultra-advanced drive controls; USB ports for hand-held devices; and ever-enhanced suspension for terrain handling.

Yet there’s still a ways to go. By 2020, we should be poised to see new motor technologies, extended-range batteries, further-advanced suspension, increased smart phone and environmental interfacing, and even electronics that connect with the cloud for diagnostics, updates and servicing.

So the answer to the question of why are power chairs lagging behind technologically is currently a positive one: They are finally getting there!

Grant Sinclair, nephew of Sir Clive Sinclair, who developed an electric tricycle in the 1980s, riding his invention, the Iris E-Trike electric tricycle, Chepstow, Wales. REUTERS Rebecca Naden

![]() Source New Mobility

Source New Mobility

| The brains behind the electric wheelchair, one of Canada’s ‘great artifacts’ |

From left to right: NRC colleagues, George Klein and Robert Owens, working on the prototype electric wheelchair in the early 1950s at NRC in Ottawa. George J. Klein, one of Canada’s most prolific inventors, is credited with dreaming up many of the key features of the electric wheelchair. The Globe and Mail

Murat Yukselir, Katherine Scarrow, Paula Wilson And Tonia Cowan, The Globe And Mail August 27, 2012

George Johann Klein was considered one of Canada’s most productive 20th-century inventors. His years of work at the National Research Council (NRC) contributed to the development of the first microsurgical staple gun, the ZEEP nuclear reactor, the international system for classifying ground-cover snow, aircraft skis, the Weasel all-terrain vehicle and the STEM antenna for the space program.

At the age of 72, he was pulled out of retirement to act as chief consultant on gear design for the CANADARM project and continued to further its development into his 80s.

But it was the electric wheelchair he developed following the Second World War that is considered his crowning achievement. Widely viewed as “one of the greatest artifacts in the history of Canadian science, engineering and invention,” the chair was revered around the world for improving the mobility and quality of life for the disabled.

Born in Hamilton, on Aug. 15, 1904, George J. Klein developed an early interest in mechanical design by watching his father, a watch and jewellery store owner, tinker away in his workshop. As a child, Klein enjoyed woodworking, but he was also fond of classical music. In his later years, he would become an accomplished violinist, performing in both Hamilton’s and Ottawa’s symphony orchestras.

Despite his talents, Klein was not, as Richard I. Bourgeois-Doyle points out in George Klein: Canada’s Great Inventor, “one of those rare 1920s technical school graduates with great potential destined for post-secondary education.” After graduating from the Hamilton Technical Institute High School (his final report card was filled with C’s, which at the time stood for ‘credit,’ one level above a failure), Klein went to study at the University of Toronto, where he graduated in 1928 with a bachelor’s degree in applied science.

He was fortunate enough, however, to have a professor like John H. Parkin who, after being appointed Director of mechanical engineering at the National Research Council, the country’s agency of scientific research and development, offered him a plum job as a researcher. Klein joined the NRC in 1929 and stayed for the next 40 years.

![]() Source The Globe and Mail

Source The Globe and Mail

| References |

George J. Klein: The Great Inventor, Bourgeois-Doyle, Richard I. Ottawa: NRC Research Press, 2004. ISBN 0-660-19322-1

NRC Helps Welcome Home a Great Canadian Innovation: Original Electric Wheelchair Returns to Ottawa National Resource Council Canada NRCC

Also see

Inventor hopes eTrike will succeed where uncle’s Sinclair failed Reuters Technology News