Spaces should be better designed for people with disabilities, says Ross Atkin

Streets need to be designed to consider people with disabilities, says Emerging Design Medal winner Ross Atkin. Dezeen spoke to him about four of his best tech-led works for people whose environments are “letting them down.”

Natashah Hitti, Dezeen 15 September 2019

London-based engineer Atkin was awarded the Emerging Design Medal last week at this year’s British Land Celebration of Design Awards for his tech-focused work that aims to help people with disabilities.

“Once I started doing research with disabled people, in streets but also at home and in schools, I realised that there were so many ways that their environments were letting them down,” Atkin told Dezeen.

“There are things that are difficult and inconvenient for them that wouldn’t be if the people who designed the environment, and the things in it, had better considered their needs.”

| Work stems from inclusive design research |

The Royal College of Art graduate was first introduced to inclusive design when he started working at the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design at the college – a research institute dedicated to projects that improve people’s lives.

The ideas developed there heavily influenced much of Atkin’s subsequent work, which spans from roadsigns for the blind to artificially intelligent DIY robots.

Atkin often incorporates assistive technology into his work, finding an “incredible thrill” in designing products that help individuals do something they couldn’t do before.

“Now is an amazing time to be working as a designer, because technology is moving so fast that it becomes possible to create new things that solve problems that couldn’t be solved previously,” said the engineer.

| Kids can benefit from playing with tech |

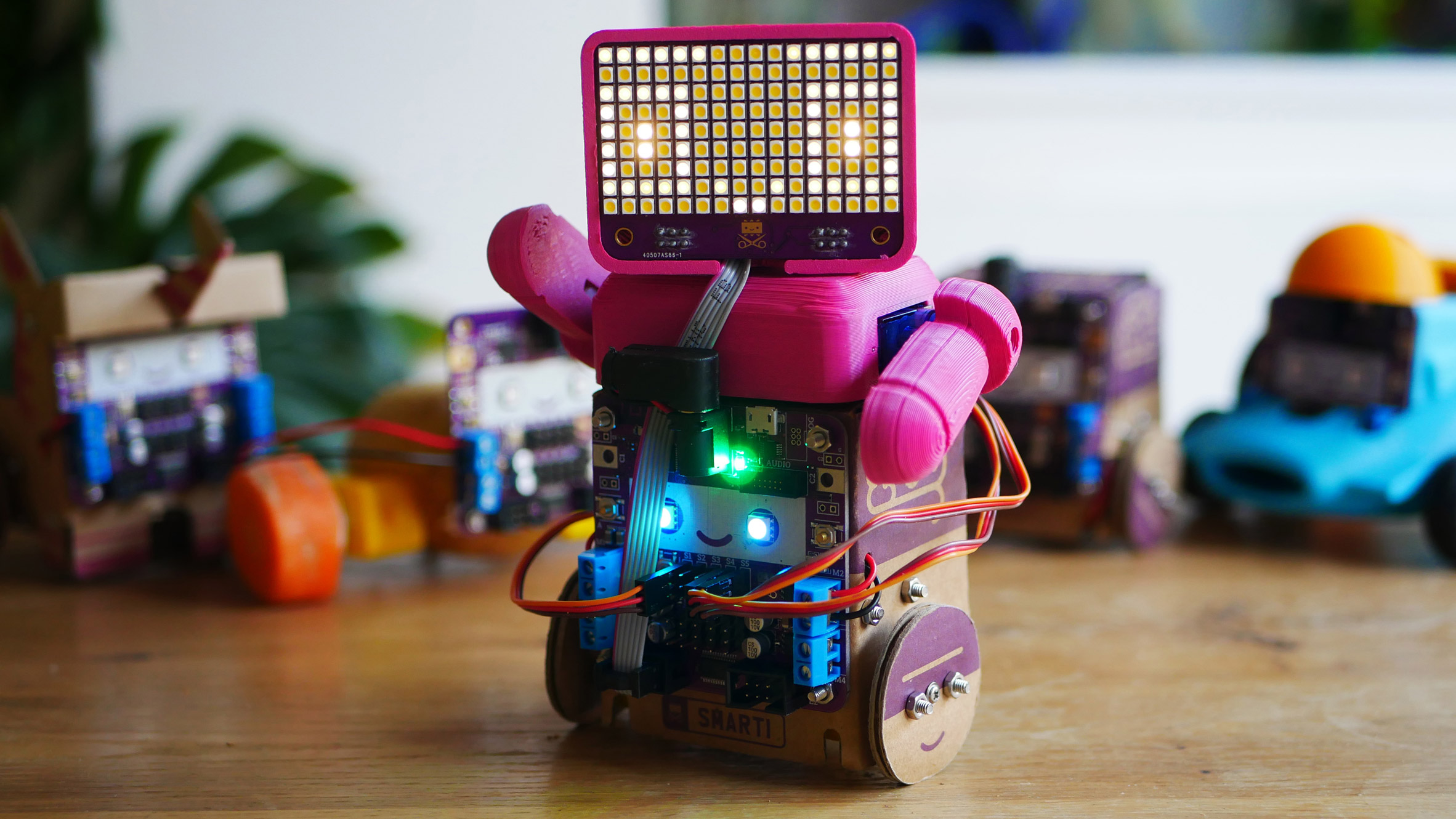

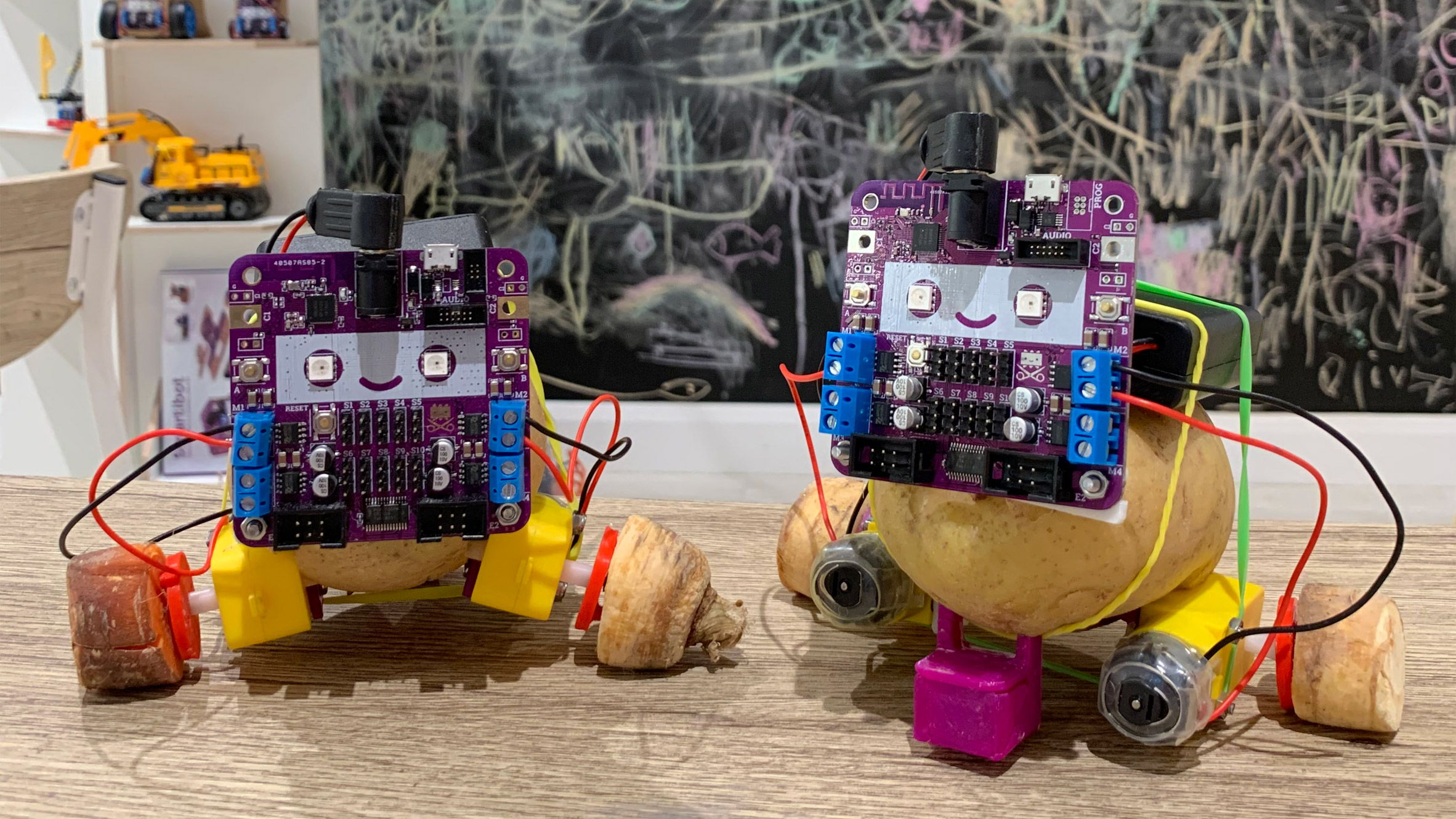

His work also acts as learning aids for children. The Smartibot, for example, allows kids to make a robot from their own Lego, or even vegetables. Atkin sees allowing children to experiment with technology as a positive thing.

“It’s easy to say ‘technology is bad for kids, they should be being creative’ without appreciating the amazing things technology can allow kids to do creatively,” he said.

“If you had told seven-year-old me that I could build a robot out of a potato and program it to chase my dog, it would have blown my mind,” Atkin added.

“The most important thing, and what makes us designers, is to always focus on the person and the problem and work out how the technology can help, rather than the other way around.”

Here, Atkin talks through four projects that best represent his practice:

| Sight Line |

Atkin describes his Sight Line project as “an illustration of careful physical and digital design working together.”

The work comprises a series of changes to the design and use of roadworks – specifically the signing and guarding equipment set out for pedestrians – in order to make them easier to navigate for people with sight loss.

Atkin added simple tactile and high-contrast visual information to roadworks equipment – changes that are designed to be as small as possible in order to minimise the cost of implementation.

In addition to these physical changes, the project also includes an app that provides digital information about any temporary changes to the street environment via audio descriptions.

Sight Line has been deployed in five UK towns and cities by seven utilities and construction companies.

| Smartibot |

As the engineer’s “most complicated product,” Smartibot is an AI-enabled cardboard robot that users can build themselves, and control with their smartphone.

Primarily comprised of a robotics platform, the Smartibot electronics are reusable, allowing users to create their own robots out of almost anything they have to hand, from Lego constructions to vegetables.

Users can also attach their phone to Smartibot and use an AI mode on the Smartibot app to tell the robot to detect certain objects, using image recognition to recognise and chase people, vehicles or pets.

Atkin sees this as a useful way of helping children understand a bit more about how AI works.

| Responsive Street Furniture adapts public spaces to suit pedestrians’ needs. This movie shows street furniture prototypes designed to make cities more adaptable for disabled people by Ross Atkins and Jonathan Scott. The furniture is on show at the Designs of the Year exhibition at London’s Design Museum. Dezeen. Youtube May 14, 2015 |

| Responsive Street Furniture |

Atkin’s Responsive Street Furniture project uses digital technology to make public infrastructure, such as street lights, crossings and bollards, automatically respond to the specific needs of pedestrians with different impairments.

Developed in partnership with Jonathan Scott at commercial landscaping specialists Marshalls, the project “shows how transformative technology could be for people with disabilities.”

“It is a big intervention, basically an operating system for the city, which I think is why it has been difficult to deploy, but I know there are so many problems it could solve if it is ever installed widely,” Atkin told Dezeen.

Users who are blind, partially sighted, deaf or hard-of-hearing select the services they would benefit from via a website. Bluetooth sensors in their smartphones, tablets or a low-cost fob tell sensors in the street furniture to activate their selected functions when they pass by.

You can see what Ayala, Caira and Nicole thought about what we made for them in the Big Life Fix Children In Need Special.

| The Big Life Fix |

The project Atkin is most proud of is his involvement in The Big Life Fix, a reality TV program that aired on BBC2 in August 2018.

The series brought together a group of leading designers to create new inventions that would improve the quality of life for people with specific needs.

“The program did a good job of accomplishing two things that I feel are important,” Atkin explained. “Firstly, it gave a more accurate and engaging portrayal of what designers and engineers actually do than any previous programs on the subject.”

“The other thing it achieved is to move the conversation around disability on TV away from senses of either pity or awe, and towards seeing disabled people as individuals who just want to do things, but need a bit more consideration from society to allow them to,” he continued.

“There is a very powerful idea called The Social Model of Disability, which holds that disabled people are disabled by their environments rather than any particular variation in their capabilities,” Atkin added. “I hope that the program illustrated how far that thinking can take you.”

| London Design Festival announces medal winners in iconeye 4 September 2019 |

Source Dezeen

| London Design Festival: Ross Atkin, Emerging Design Medal Winner 2019. | 59″ Trailer. Zetteler. Vimeo 5 September 2019 |

Ross Atkin is the winner of the Emerging Design Medal, which recognises designers making an impact within five years or so of graduation. Much of Atkin’s work focuses on making it easier for disabled people to live independently, with his designs including responsive street furniture that adapts lighting or crossing signals automatically to provide assistance, and Sight Line, a system for improving the accessibility of roadworks, particularly for people who are visually impaired. He also works to introduce design and engineering to children, and has created a range of robots in materials including cardboard and Lego.

On winning the award, Atkin said, ‘It’s beyond my imagination to be in the company of true legends of design, and it also is an amazing privilege to be representing the world of inclusive design on such a prominent platform as London Design Festival. I look forward to more designers from that world being recognised in the future.’

| Further reading |

Rethinking disability: the social model of disability and chronic disease, Goering S. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015 Jun;8(2):134-8. doi: 10.1007/s12178-015-9273-z. Full text

Also see

Microsoft’s trickiest product might be its most important Fast Company

The Social Model vs The Medical Model of Disability Disability Nottinghamshire