Pre-operative exercise boosts TKA outcomes

An evidence-based exercise regimen, designed to enhance knee strength and the ability to complete functional tasks, may speed recovery following total knee arthroscopy, TKA, in patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Evoke unloading knee brace

by Kent Brown MS CSCS, Joseph A. Brosky Jr. PT MS SCS, Dave Pariser PT PhD and Robert Topp RN PhD, Lower Extremity Review March 2010

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a condition characterized by joint pain and dysfunction caused by loss of articular cartilage with remodeling of subchondral bone.[1] The disease is one of the most common chronic health problems, currently affecting more than 27 million U.S. residents, a 29% increase from the estimated number of OA cases in 1995.[2,3] With 59% of adults over age 65 affected by this disease, its impact is projected to increase with the aging of the population.[4] After the age of 40, the incidence of OA increases rapidly in all joints, and in most joints the incidence is greater among women than men.[5] Osteoarthritis disables about 10% of individuals who are over the age of 60, lowering the quality of life of more than 20 million people in the U.S., and it costs more than $60 billion per year.[5]

Knee OA has been shown to be a risk factor for disability.[6] Osteoarthritis frequently affects weight-bearing joints, with the knee being most frequently involved joint.[7] Characteristics associated with knee OA include decreased quadriceps strength, decreased functional ability, and increased fatigue and joint pain.[8,9] Progression of these symptoms often leads to decreased mobility, deconditioning, and further decline in functional ability, all of which contribute to decline in the patient’s quality of life. Patients with knee OA may have limitations that impair their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), such as walking, bathing, dressing, using the toilet, and performing normal household chores.[10]

The specific causes of knee OA are not completely known, but it appears that biomechanical abnormalities and/or stresses and biochemical changes in the articular cartilage and synovial membrane are important in its pathogenesis.[8,10] The clinical classification of OA includes symptoms of persistent joint pain and stiffness along with joint degeneration.[1] Pain from knee OA may increase with changes in barometric pressure, fluctuations in ambient temperature, and increased physical activity.[1]

Categorization of the severity of OA is normally made from radiographic evidence of attrition of the articular cartilage and changes in the underlying subchondral bone.[8] However, there exists a poor association between radiographic signs of joint damage and the pain or functional limitations experienced by patients with knee OA.[11] Patients who present with severe radiographic joint damage may report little or no pain, while others with severe pain may have minimal evidence of degenerative changes in the affected joint.[12] Similarly, Thomas et al [11] concluded that severity of radiographic knee OA is of limited value over clinical symptoms, including pain and functional ability, when predicting which knee OA patients will experience progressive or persistent functional difficulties. Whereas radiographic signs of knee OA seem unrelated to joint pain, quadriceps weakness is a very common symptom reported by patients with knee OA, and it is a better determinant of progression of disease and the presence of knee pain.[13,14]

| Total knee arthroplasty |

Once a patient develops OA, the disease will persist for the remainder of the lifespan, and the severity of pain and disability generally increases.[5,6] Knee OA is initially treated pharmacologically in an attempt to control the joint pain and preserve functional ability, but frequently the disease progresses to a level at which total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is indicated.[15] This treatment for knee OA can reduce pain, maintain or improve joint mobility, and limit functional impairment.[10] Total knee arthroplasty commonly involves prolonged rehabilitation.[15,16 ]

Osteoarthritis accounts for 55% of all arthritis-related hospitalizations, representing more than 409,000 hospitalizations involving OA as the principal diagnosis.[17] Knee and hip replacement procedures represent 35% of all arthritis-related procedures during hospitalization.[17] Lethbridge-Cejku et al [17] estimated that the costs of knee and hip replacements as early as 1997 was close to $7.9 billion. The total cost attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the U.S. in 2003 was approximately $128 billion, including $80.8 billion in direct costs (i.e., medical expenditures) and $47 billion in indirect costs (i.e., lost earnings). This amount equaled 1.2% of the 2003 U.S. gross domestic product.[18] It is projected that in the year 2016, more than one million TKAs will be performed in the U.S.,[19] and this number is predicted to increase by 600% to more than 3.4 million procedures by 2030.[20]

Exercise has been shown to be beneficial for older adults with OA,[6,21] because it helps to decrease pain and aids in maintaining joint function.[6] Therapeutic exercise for increasing muscle strength in patients with knee OA is recommended within several guidelines.[10,22] According to the best practices statement published by the American College of Sports Medicine, physical activities that include planned exercise offer opportunities for individuals to extend their years of independence and reduce their functional limitations.[23,24]

Cress states that regular participation in physical activities is one of the best ways for older adults, including those with knee OA, to maintain their independence and increase quality of life in old age.[23] Among adults with OA, participation in regular physical activity has been shown to reduce the rate of functional decline.[24] Ettinger and others state that appropriate exercise offers benefits in treating the patient with knee OA, including decreased pain, improved function, and increased self-efficacy.[25,26] Improvements in the measures of knee pain, strength, and the ability to complete functional tasks have been associated with various exercise interventions in patients with knee OA,[25,27] with as little as four to eight weeks of moderate-intensity training.[28-30]

| The role of exercise and TKA |

Although exercise is considered by many to be a cornerstone of rehabilitation following TKA, little attention has been paid to the role of exercise in preparation prior to TKA surgery. The concept of preparing the body prior to a stressful event such as TKA surgery has been termed “prehabilitation.” [31] The theory that prehabilitation can improve TKA outcomes is supported by empirical studies that indicate that preoperative knee strength is a consistent predictor of postoperative knee strength [30] and functional ability among TKA patients.[32] Other previous researchers have concluded that exercise interventions can improve the ability to complete functional tasks, increase knee strength, and reduce knee pain among nonsurgical patients with knee OA.[27]

Based on these previous findings, it seems reasonable to postulate that enhancing knee strength and the ability to complete functional tasks prior to TKA surgery through exercise interventions might accelerate the rate of the patient’s recovery from a TKA procedure. A number of studies have examined the effects of preoperative exercise interventions on postoperative outcomes.[26,33-39] Data on the direct effects of prehabilitation TKA exercise interventions are scarce,[26] although recent studies show the benefits of appropriate prehabilitation exercise interventions in treating patients with OA prior to TKA.[30,40,41]

In a recent review, Barbay concluded that preoperative exercise had some postoperative benefit to total knee or hip arthroplasty patients.[35] However, given the lack of strong research evidence in this area, the author cautioned that she could support only a pragmatic recommendation for preoperative exercise prior to total hip or knee arthroplasty. Nonetheless, the prevailing literature and the theory of prehabilitation support the efficacy of knee OA patients engaging in exercise that improves their strength and functional ability prior to TKA in anticipation of accelerating their recovery from this surgery.[42]

| A model program of prehabilitation |

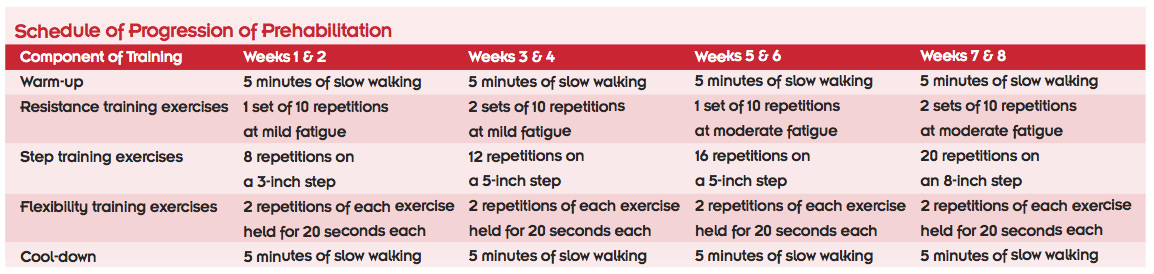

The program of prehabilitation for patients with knee OA is based on previous studies for older adults who are scheduled for TKA.[43] The prehabilitation program would optimally be initiated eight weeks prior to surgery and consist of five components performed during three sessions per week. Each session should include a warm-up, 10 resistance exercises, four step exercises, six flexibility exercises, and a cool-down (see Appendix A). The program of prehabilitation should progress the patient from his or her initial level of fitness to higher levels of fitness over the duration of the training period (see Appendix B).

During weeks one and two, an individual training session is recommended to consist of five minutes of warm-up, 15 minutes of resistance training, 10 minutes of step training, 15 minutes of flexibility exercises, and five minutes of cool-down. The warm-up consists of slow walking to increase blood flow to the muscles of the legs, trunk, and arms. Following the warm-up, patients complete 10 dynamic muscle-strengthening exercises: squats, ankle dorsi- and plantar flexions, hamstring flexion, hip abduction, hip extension, bicep curls, triceps extensions, chest press, and seated row. These exercises are designed to improve both lower and upper body strength, which is essential to completing functional tasks following TKA. The muscles of the lower body include the quadriceps and hamstring groups, and the upper body muscles include the deltoids of the shoulder and biceps and triceps of the upper arm.

During the first training week, each patient performs one set of 10 repetitions of each strengthening exercise using elastic resistance (e.g., Theraband) with sufficient resistance to produce subjective “mild” fatigue following the final repetition. Individual training then progresses by adding another set or adding more resistance, or both, until weeks seven and eight, when the patient performs two sets of 10 repetitions of each exercise using elastic resistance to produce “moderate” fatigue following the final repetition with a two-minute rest between sets (approximately 20 minutes).

Following completion of the resistance exercises, patients then complete four step training exercises within each training session. These exercises include going up and down a single step forward and backward and then sideways from the left and from the right. Many patients may be unable to perform the backward step-ups because of poor balance or limited knee range of motion, and these may need to be modified or omitted for safety. During the first week of the prehabilitation program, patients are advised to complete eight repetitions of each of the step exercises using a 4-inch step. The number of repetitions and the height of the step of each of these step exercises are increased over the eight-week prehabilitation intervention, so that during the eighth week, patients are doing 20 repetitions of each step exercise using an 8-inch step.

After the step training exercises, within each session of prehabilitation, the patient is directed to complete six flexibility exercises. Over the entire duration of the eight-week training program, each flexibility exercise includes two 20-second repetitions of static stretching. The six exercises, designed to improve flexion-extension range of motion in the hip and knee, are hamstring stretching, quadriceps stretching, active hip flexion, passive knee flexion, passive knee extension (e.g., heel prop), and calf stretching.

The cool-down consists of five minutes of slow walking, which includes movements of the muscles of the legs, trunk, and arms. If the patient is unable to complete the initial level of training or is unable to progress at any week in the eight-week training schedule, an individualized training program should be developed consistent with his or her level of training ability.

| Kent Brown MS CSCS is chair of exercise science in the Lansing School of Nursing and Health Sciences at Bellarmine University in Louisville, KY. Joseph A. Brosky Jr. PT MS SCS is an associate professor of physical therapy and Dave Pariser PT PhD is an assistant professor of physical therapy at the same institution. Robert Topp RN PhD is assistant dean for research and Shirley B. Powers Endowed Chair in Nursing Research at the University of Louisville. |

Source Lower Extremity Review

Prehabilitation Training Program for Knee OA Patients Scheduled for TKA, Lower Extremity Review. March 2010

The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning after total knee arthroplasty, Topp R, Swank AM, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A. PM R. 2009 Aug;1(8):729-35. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.06.003.

| References |

- Osteoarthritis, Buckwalter JA, Martin JA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006 May 20;58(2):150-67. Epub 2006 Mar 13. Review.

- Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults-United States, 1999, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001 Feb 23;50(7):120-5. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001 Mar 2;50(8):149.

- Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II, Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Jordan JM, Katz JN, Kremers HM, Wolfe F; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan;58(1):26-35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176.

- Prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among adults-United States, 2001, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 Oct 25;51(42):948-50.

- The impact of osteoarthritis: implications for research, Buckwalter JA, Saltzman C, Brown T. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Oct;(427 Suppl):S6-15. Review.

- Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis, Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell R, Pollak N, Huber G, Sharma L. Gerontologist. 2004 Apr;44(2):217-28.

- Resistance training for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis and malalignment, King LK, Birmingham TB, Kean CO, Jones IC, Bryant DM, Giffin JR. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Aug;40(8):1376-84. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816f1c4a.

- The role of muscle weakness in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis, Hurley MV. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999 May;25(2):283-98, vi. Review.

- Current perspectives on the clinical presentation of joint pain in human OA, Creamer P. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;260:64-74; discussion 74-8, 100-4, 277-9. Review.

- Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines, [No authors listed] Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Sep;43(9):1905-15.

- Predicting the course of functional limitation among older adults with knee pain: do local signs, symptoms and radiographs add anything to general indicators? Thomas E, Peat G, Mallen C, Wood L, Lacey R, Duncan R, Croft P. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Oct;67(10):1390-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080945. Epub 2008 Jan 31.

- Do clinical findings associate with radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee? Claessens AA, Schouten JS, van den Ouweland FA, Valkenburg HA. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990 Oct;49(10):771-4.

- Effect of thigh strength on incident radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in a longitudinal cohort, Segal NA, Torner JC, Felson D, Niu J, Sharma L, Lewis CE, Nevitt M. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Sep 15;61(9):1210-7. doi: 10.1002/art.24541.

- Physical function and properties of quadriceps femoris muscle in men with knee osteoarthritis,

Liikavainio T, Lyytinen T, Tyrväinen E, Sipilä S, Arokoski JP. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Nov;89(11):2185-94. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.04.012. - A prospective population-based study of the predictors of undergoing total joint arthroplasty, Hawker GA, Guan J, Croxford R, Coyte PC, Glazier RH, Harvey BJ, Wright JG, Williams JI, Badley EM. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Oct;54(10):3212-20.

- 2002 National Hospital Discharge Survey, DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. Adv Data. 2004 May 21;(342):1-29.

- Hospitalizations for arthritis and other rheumatic conditions: data from the 1997 National Hospital Discharge Survey, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Helmick CG, Popovic JR. Med Care. 2003 Dec;41(12):1367-73.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Data and Statistics, Kentucky. 2007.

- An outstanding scientific knee paper from the specialty societies, O’Connor MI, Fehring TK. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Aug;91 Suppl 5:62-3. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00414. No abstract available.

- Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030, Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Apr;89(4):780-5.

- Physical activity programs and behavior counseling in older adult populations, American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Nov;36(11):1997-2003. Review..

- Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises and manual therapy in the management of osteoarthritis, [No authors listed] Phys Ther. 2005 Sep;85(9):907-71. Review.

- Best practices for physical activity programs and behavior counseling in older adult populations, Cress ME, Buchner DM, Prohaska T, Rimmer J, Brown M, Macera C, Dipietro L, Chodzko-Zajko W. J Aging Phys Act. 2005 Jan;13(1):61-74. Review.

- Effects of activity strategy training on pain and physical activity in older adults with knee or hip osteoarthritis: a pilot study, Murphy SL, Strasburg DM, Lyden AK, Smith DM, Koliba JF, Dadabhoy DP, Wallis SM. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Oct 15;59(10):1480-7. doi: 10.1002/art.24105.

- A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST), Ettinger WH Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, Applegate W, Rejeski WJ, Morgan T, Shumaker S, Berry MJ, O’Toole M, Monu J, Craven T. JAMA. 1997 Jan 1;277(1):25-31.

- Effect of preoperative exercise on measures of functional status in men and women undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty, Rooks DS, Huang J, Bierbaum BE, Bolus SA, Rubano J, Connolly CE, Alpert S, Iversen MD, Katz JN. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Oct 15;55(5):700-8.

- The effect of dynamic versus isometric resistance training on pain and functioning among adults with osteoarthritis of the knee, Topp R, Woolley S, Hornyak J 3rd, Khuder S, Kahaleh B. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Sep;83(9):1187-95.

- Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trial, Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Feb 1;132(3):173-81.

- Total knee replacement: the joint of the decade. A successful operation, for which there’s a large unmet need, Moran CG, Horton TC. BMJ. 2000 Mar 25;320(7238):820.

- Predictors of functional task performance among patients scheduled for total knee arthroplasty, Brown K, Kachelman J, Topp R, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A, Swank AM. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Mar;23(2):436-43. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318198fc13.

- Prehabilitation in preparation for orthopaedic surgery, Ditmyer MM, Topp R, Pifer M. Orthop Nurs. 2002 Sep-Oct;21(5):43-51; quiz 52-4. Review.

- Predicting functional ability following total knee replacement, Presented at Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science 2008, Topp R, Swank AM, Quesada PM, et al. National State of the Science Congress in Nursing Research, Washington DC, October 2008.

- Prehabilitation before knee arthroplasty increases postsurgical function: a case study, Jaggers JR, Simpson CD, Frost KL, Quesada PM, Topp RV, Swank AM, Nyland JA. J Strength Cond Res. 2007 May;21(2):632-4.

- Preoperative physical therapy in primary total knee arthroplasty, Rodgers JA, Garvin KL, Walker CW, Morford D, Urban J, Bedard J. J Arthroplasty. 1998 Jun;13(4):414-21.

- Research evidence for the use of preoperative exercise in patients preparing for total hip or total knee arthroplasty, Barbay K. Orthop Nurs. 2009 May-Jun;28(3):127-33. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0b013e3181a46a09.

- Preoperative quadriceps strength predicts functional ability one year after total knee arthroplasty, Mizner RL, Petterson SC, Stevens JE, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. J Rheumatol. 2005 Aug;32(8):1533-9.

- The effect of preoperative exercise on total knee replacement outcomes, D’Lima DD, Colwell CW Jr, Morris BA, Hardwick ME, Kozin F. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996 May;(326):174-82.

- Exercise improves early functional recovery after total hip arthroplasty, Gilbey HJ, Ackland TR, Wang AW, Morton AR, Trouchet T, Tapper J. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003 Mar;(408):193-200.

- Prehabilitation versus usual care before total knee arthroplasty: A case report comparing outcomes within the same individual, Brown K, Swank AM, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A, Topp R. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010 Aug;26(6):399-407. doi: 10.3109/09593980903334909.

- Prehabilitation before total knee arthroplasty increases strength and function in older adults with severe osteoarthritis, Swank AM, Kachelman JB, Bibeau W, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A, Topp RV. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Feb;25(2):318-25. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318202e431.

- Improve Function before knee replacement surgery, Topp R, Page P. Functional U 2009;7(2):1-8.

- The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning after total knee arthroplasty, Topp R, Swank AM, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A. PM R. 2009 Aug;1(8):729-35. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.06.003.

- Effect of resistance training on strength, postural control, and gait velocity among older adults, Topp R, Mikesky A, Dayhoff NE, Holt W. Clin Nurs Res. 1996 Nov;5(4):407-27.