How athletes regenerate: Results from competitive sports

What does an Olympic athlete do after the competition? He runs another round to warm down, goes to the sauna or has a massage. Sports scientists have analysed the effect these activities have on the body.

RUB researchers have been analysing which recovery strategies are effective after sport. RUB, Damian Gorczany

by Katharina Gregor, RUBIN Science Magazine August 2, 2016

Sweat is dripping, muscles are burning and ambition is running high: the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Top athletes have been preparing for this moment for years. Rigorous training and discipline pay out eventually – in meters for shot-putters, in seconds for swimmers and in kilos for weightlifters. However, training sessions are not the only factor that decides about an athlete’s performance. What happens afterwards is just as relevant: namely the recovery phase.

Regeneration after a competition or after training is important. Muscle activity, concentration and perspiring have taken their toll on body and mind. An athlete has to recover, in order to be able to give their all in the next training session or competition.

Rest, cooling-down and massage are three possible relaxation measures. But what is the most effective way for athletes to recover? And are there any methods that are recommended for all sports?

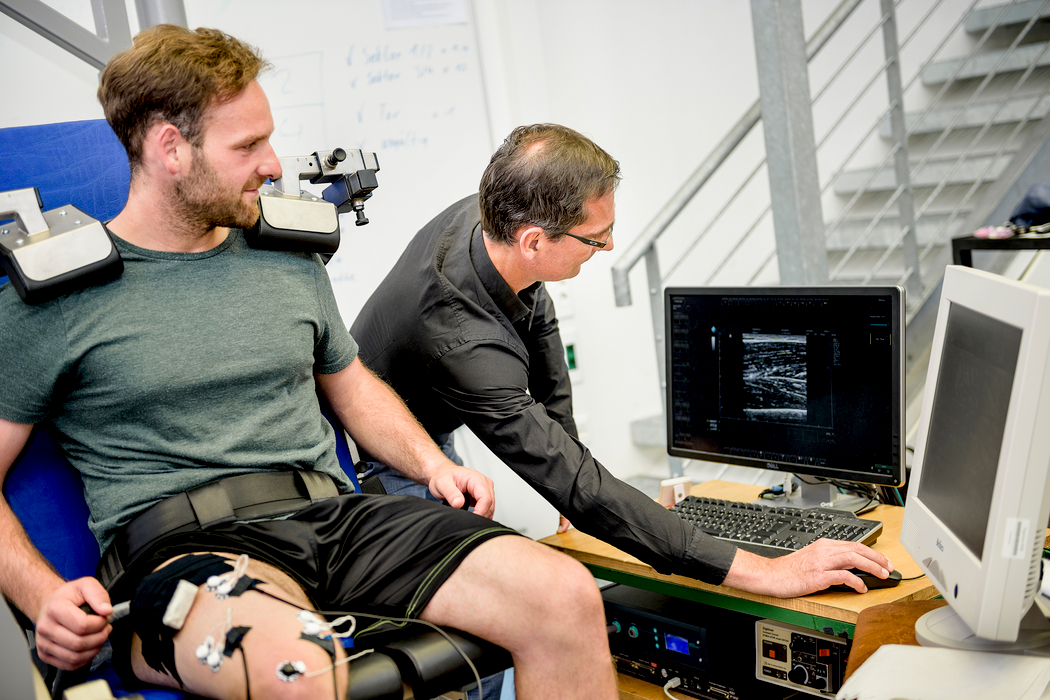

Researchers can also use ultrasound to measure how muscles behave under maximum tension. RUB, Damian Gorczany

In collaboration with researchers at Saarland University and the University of Mainz, training and exercise science researcher Prof Dr Alexander Ferrauti and sport psychologist Prof Dr Michael Kellmann are searching for answers to these questions. In the joint project Management of Regeneration in Elite Sports – Regman, they have conducted studies into this subject for several years.

“In the first place, we had to find indicators of fatigue that apply specifically to different sport types and groups. After all, exertion levels can vary among different types of sport,” says Ferrauti. Utilizing jump tests, questionnaires and blood test, the research team rendered regeneration processes measureable and verifiable.

Using motoric tests, such as jump tests, the researchers from Bochum recorded the athletes’ performance shortly after an intensive training session as well as after the recovery phase. They evaluated the height and efficiency of the jump, in order to gauge the recovery status in the respective phase.

Jump efficiency is calculated using the height of the jump and the time the person was in contact with the ground before the jump. Thus, Ferrauti and his colleagues were able to measure if and in what way performance capability is restored following different regeneration strategies. If an athlete recovered very well, he can jump more efficiently than immediately after the training session.

In addition to performance tests, the researchers conducted blood tests after the training sessions and the regeneration phase. One factor is increased levels of the muscle enzyme creatine kinase in the blood. This enzyme is an indicator of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). DOMS is caused by miniscule injuries in muscle cells. Scientists refer to them as micro traumata. It takes several days for the enzyme levels to fall again.

For their study, the research team visited top athletes in their training camps and in Olympic centres. Participants in the Regman project included the German weightlifters and the men’s national volleyball team.

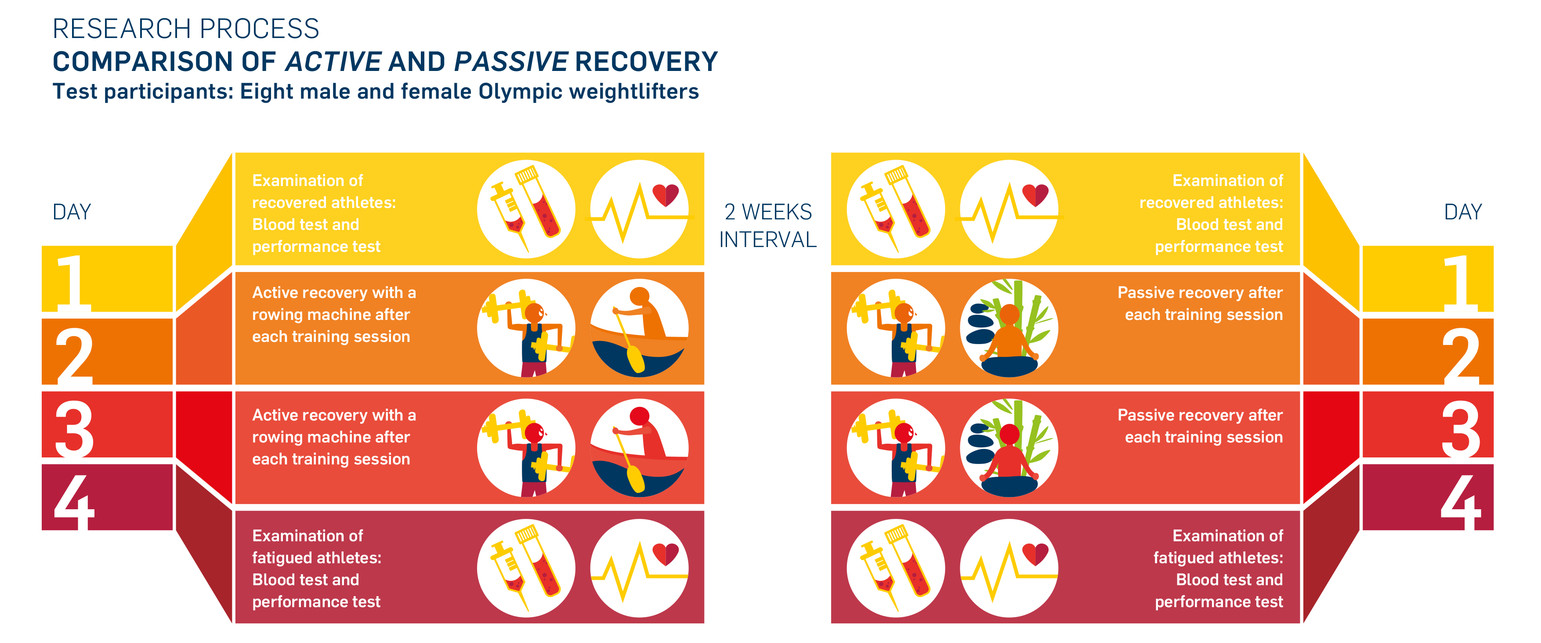

Using athletes as study subjects, the researchers analysed which recovery measures are particularly effective. For weightlifters, Ferrauti, Kellmann and their colleagues compared, among other aspects, the differences between active and passive recovery. To this end, the researchers used performance tests and blood tests to gather data from athletes in their recovered state prior to a two-day training block.

The participants trained twice a day. Following each training session, the weightlifters underwent active or passive recovery – depending on the test group to which they were assigned. For active recovery, they used a rowing machine, as recommended by the German national coach. For passive recovery, the strength athletes simply relaxed.

| Fig. 4. One participant group recovered actively in the first part of the study, before switching over to passive recovery after an interval of two weeks. Another group did it the other way round. Agentur der RUB, Zalewski |

One day after the full training block, the researchers again recorded the values relevant for evaluating regeneration. The researchers studied the same training block two weeks later with the same athletes. The athletes who had previously spent their recovery phase at the rowing machine now used the passive method, and vice versa. Scientists call this a cross-over design.

In another study, the research team examined other regeneration measures. They compared passive regeneration with combined recovery programmes that included, for example, stretching, massages and ice-water baths.

For this purpose, the researchers even organised a tennis tournament – the Regman Open. They recorded performance, individual results and running intensity of semi-professional tennis players, in order to analyse the effect of specific recovery strategies.

The mean value of the blood tests and motoric performance tests demonstrated that an exceptionally effective regeneration measure does not exist. However, individual values indicated that active regeneration or an ice bath boost the performance in some athletes.

Athletes considered massages to be beneficial, even though they did not result in an increased performance. Consequently, subjective perception should be allowed for in the recovery process. The results also show that regeneration measures have a different effect on different individuals.

Other recovery strategies, such as wearing compression garments, yielded similar results. There is therefore no generally applicable regeneration measure to boost performance.

RUB, Damian Gorczany

“Regeneration is a highly individual process,” says Kellmann. Each athlete should choose the measure that he or she prefers and that is best suited to their respective type of sport. Alexander Ferrauti lists some examples: “After a match at the very hot Australian Open, sending a tennis player into the sauna makes as little sense as putting a swimmer into a water tub.”

The researchers advise athletes to identify the method that is beneficial for them. “Still, it is crucial to test and practise several measures prior to a tournament or competition,” says Michael Kellmann. In order to achieve optimal regeneration effects, an acclimatisation phase is advisable. “The most important thing is: the individual athlete has to embrace the respective method.”

Athletes familiar with various recovery strategies will be able to adapt to the conditions on location during the competition. “The weightlifters in Rio probably won’t have a rowing machine at their disposal in their locker rooms. They will have to take other measures for active recovery,” says the researcher from Bochum.

Even though the Regman Project will be wrapped up in late 2016, the researchers are going to continue their studies into regeneration management. “We intend to set up a toolbox with measures for different types of sport,” says Kellmann. It will be designed to evaluate individual strategies for specific types of sport. Thus, it will enable athletes and coaches to choose specific measures best suited for their purpose.

The research team is, moreover, considering developing an app for recovery management. Athletes may then use it to analyse their own recovery state. “But that’s all still up in the air.”

Source Ruhr Universität Bochum via Science Daily

Source Ruhr Universität Bochum via Science Daily

Also see

Effective recovery in competitive sports Ruhr Universität Bochum, RUBIN