Pectus carinatum: surgery or bracing

3D Scan, Braceworks 2016.

Mary E Cataletto MD, Chief Editor: Denise Serebrisky MD, Medscape Updated April 20, 2018

| Overview |

| Background |

Pectus carinatum (ie, carinatum or keel-shaped deformity of the chest) is a term used to describe a spectrum of protrusion abnormalities of the anterior chest wall.

The deformity may be classified as either chondrogladiolar or chondromanubrial, depending on the site of greatest prominence. Lateral deformities are also possible.

Hippocrates described the carinatum deformity as a “sharply pointed chest” and reported that patients became “affected with difficulty breathing.” Symptomatic patients report dyspnea and decreased endurance. Some develop rigidity of the chest wall with decreased lung compliance, progressive emphysema, and increased frequency of respiratory tract infections.[1] Many affected patients have no physical complaints; however, concerns about body image have been associated with low self-esteem and a decreased mental quality of life.[2] Cosmetic concerns can be significant factors in opting for correction.

Barrel chest deformities with increased anteroposterior (AP) chest diameters can be seen in obstructive forms of chronic pulmonary disease, such as cystic fibrosis and untreated or poorly controlled asthma.

| Pathophysiology |

Until recently, most cases of pectus carinatum deformity were thought to be asymptomatic. However, little is known about the cardiopulmonary function. In 1989, Derveaux reported a series of patients with no significant preoperative or postoperative respiratory compromise.[3]

However, some patients develop a rigid chest wall, in which the AP diameter is almost fixed in full inspiration. In these patients, respiratory efforts are less efficient. Vital capacity is reduced, and residual air is increased. Alveolar hypoventilation may ensue, with arterial hypoxemia and the development of cor pulmonale. As the lungs lose compliance, incidence of emphysema and frequency of infection are increased.

Most recently, Fonkalsrud (2008) reported his personal experience of 260 patients, all of whom were symptomatic.[4] Symptoms that were reported included dyspnea, exertional tachypnea, and reduced endurance.In 1990, Iakovlev and colleagues studied the cardiac functions of 70 patients with pectus carinatum deformity.[5] Mitral valve prolapse was identified in 97%. Rhythm disturbances and decreased myocardial contractility were less frequently observed, along with other cardiac and hemodynamic changes. Cardiac and hemodynamic changes were more commonly observed in patients with chondromanubrial prominence.

| Epidemiology |

| Frequency |

United States

Pectus excavatum is more common than the carinatum deformity. The overall prevalence of pectus carinatum is estimated at 0.06%.[6] Fonkalsrud (2008) reported that at least 25% patients have a positive family history of chest wall deformity.[4] Pectus carinatum can also be seen in association with Marfan syndrome and congenital heart disease.

International

The percentage of chest wall deformities represented by pectus carinatum are greater in reports from Brazil [7] and Argentina.[8]

| Mortality/Morbidity |

Psychological and cosmetic concerns are the most prominent reasons for initial consultation. However, Fonkalsrud (2008) reported that surgical repair is rarely performed only for cosmetic reasons.[4] Morbidity in later years includes cardiac and hemodynamic changes.

| Race |

The conditions is more frequent in whites and is uncommon in blacks and Asians.

| Sex |

Males are affected 4 times more frequently than females. Because this deformity may occur either in isolation or as part of a syndrome, identifying a single etiology for the male predominance is difficult.

| Age |

Although pectus carinatum has been described at birth, it is most frequently identified in mid childhood. The deformity often worsens during the adolescent growth spurt.

| Clinical Presentation |

| History |

Parents or the patient may report that pectus carinatum has been present since birth or early childhood, but most children present at age 11-15 years.

The degree of deformity may worsen during adolescence, and most patients are asymptomatic.

Once adult growth has occurred, the severity of the deformity generally remains stable.

Symptomatic patients report exertional dyspnea and tachypnea as well as decreased endurance. In one series, asthmatic symptoms were reported by 22% of patients.[4]

Musculoskeletal chest pain and tenderness when lying in the prone position can also occur.[9]

Patients may be affected by low self-esteem, poor body image, and decreased mental quality of life.[2]

| Physical |

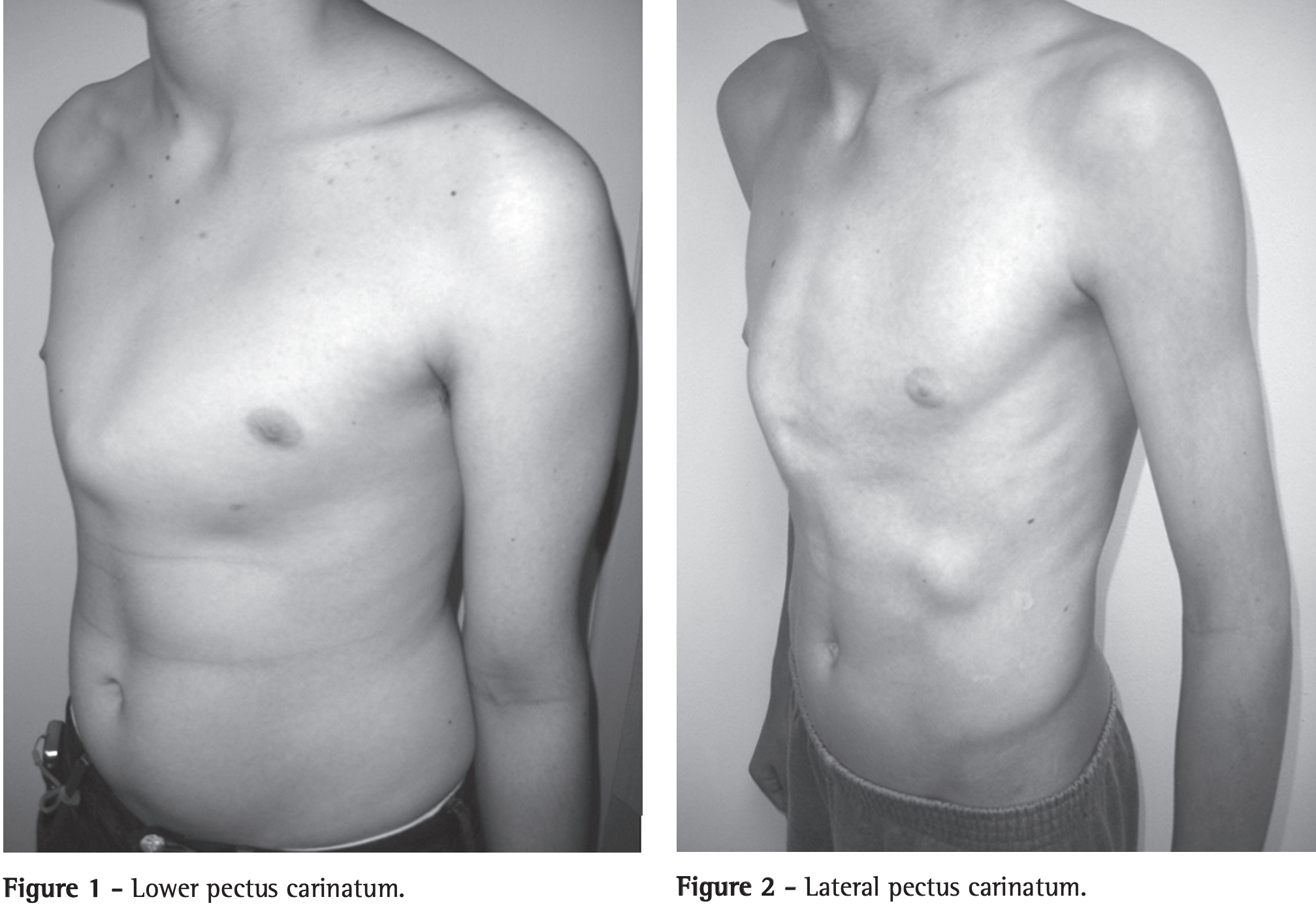

Two main types of pectus carinatum deformities have been described: chondrogladiolar and chondromanubrial. The most common is the chondrogladiolar form, in which there is a symmetric protrusion of the sternum and costal cartilages.[9]

Some authors think that a lateral category should also be included. The image below shows an example of a child with a lateral deformity.

In addition to the descriptive findings of anterior chest wall prominence, poor chest wall expansion with inspiration may be observed.

| Pectus carinatum. Marlos de Souza Coelho, Paulo de Souza Fonseca Guimarães. 2007;33(4):463-474. Brazilian Journal of Pulmonology |

| Causes |

Etiology has not been established; however, the increased incidence of positive family history and associated anomalies has suggested an abnormality in connective tissue development.[10]

Pectus carinatum deformities are associated with overgrowth of the rib cage during development of the chest wall.

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Diagnostic Considerations |

Diagnosis of pectus carinatum is clinical and is based on descriptive findings identified during the physical inspection of the chest. It may occur as an isolated anomaly, in association with congenital heart disease, or with another skeletal anomaly (20% scoliosis). Mixed deformities can be observed in Poland syndrome. Approximately 25% of patients have a positive family history of chest wall deformity. Less frequently, pectus carinatum has been associated with Morquio syndrome, hyperlordosis, and kyphosis.

| Workup |

| Imaging Studies |

Radiographic imaging should include 2 view chest radiographs: posteroanterior and lateral images. A chest radiograph of a patient with pectus carinatum is shown in the image below.

Radiograph: Pectus carinatum (pigeon chest), basal pneumonia. © Institut für Diagnostische, Interventionelle und Pädiatrische Radiologie, Inselspital Bern

Additional imaging with either a chest CT scan or MRI may also be helpful. CT scanning of the chest in an individual with pectus carinatum reveals an increased anterioposterior chest wall diameter.[11]

Figure 1. Measurement of the sternal rotation angle. The sternal rotation angle was measured as the maximum angle of the sternal slope against the baseline of the thorax. Patients with a >10° angle of sternal rotation were regarded as having asymmetric pectus carinatum. In this patient, the sternal rotation angle is 27° and the right side is the more protruded than the left. Park CH, Kim TH, et al.

The Haller method may be used to determine severity index, as follows: width of the chest divided by distance between the sternum and spine at the same level; this may help to predict those individuals who will benefit from surgical intervention.

| Other Tests |

In patients with pectus carinatum, pulmonary function studies may be tailored to address concerns about clinical symptoms and the appearance of the chest wall upon examination. Data on pulmonary and exercise physiology in patients with pectus carinatum deformities are limited. However, children with barrel chests usually have obstructive ventilatory defects. This underscores the importance of preforming complete pulmonary function testing, including prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusion capacity. Exercise testing may complement these studies.

In 1982, Castile described one patient who reported exercise intolerance in his series of symptomatic pectus deformities.[12] His pulmonary function studies revealed flow rates and lung volumes within the reference range. Derveaux’s 1989 series also reported a patient with no significant respiratory compromise at the time of his study.[3]

Progressive exercise studies may also be helpful in evaluating the exercise-related symptoms and exertional tolerance.

Electrocardiography and echocardiography may be considered if congenital heart disease is suspected. Iakovlev’s study reported 70 patients with pectus carinatum deformity. Of these, 97% had echocardiographically documented mitral valve prolapse.[5] Hemodynamic and cardiodynamic changes were also observed in some patients, as well as decreased myocardial contractility. These abnormalities were more frequently observed in the patients with pigeon breast.

Scoliosis series may be considered if clinical features are suggestive of this diagnosis.

Chromosomal analysis and metabolic testing may also be considered if other dysmorphic signs are identified.

| Treatment |

| Medical Care |

Most motivated patients with pectus carinatum, especially those younger than 18 years with malleable chest walls, benefit from orthotic bracing, and this is generally the first line of therapy.[13,14] Success rates of 65-80 % and long-term outcomes with orthotic bracing alone are encouraging.[9]

A study by Lee at el (2012) describes the preliminary results of 98 children treated using the Calgary Protocol, which involves a self-adjustable, low-profile bracing system used in 2 phases. The first phase involves 24 h/d bracing until correction is achieved. The second phase is a maintenance phase during which the brace is worn only at night until axial growth is complete.

Twenty-three children completed treatment with good patient satisfaction and improved appearance, suggesting that when used in this fashion, it is an effective treatment for pectus carinatum. Therapy failed in 42 children, owing to either noncompliance or they were lost to follow-up. Two required surgical intervention after bracing failed to correct the problem. Additional studies and follow-up of the children still on protocol is important.[15] A study by Wahba et al reported that less intensive bracing.[16]

For older patients with more rigid chest walls, bracing may not be effective and surgery may be the initial consideration.

Casting followed by bracing or bracing alone eliminates the risks of surgery and anesthesia and does not preclude surgery if unsuccessful.

| Surgical Care |

| Endoscopic resection of costal cartilage with a sternal osteotomy |

Because many corrections are performed for cosmetic reasons, decreasing the size of incisions is important.

In 1997, Kobayashi reported 2 patients in whom the pectus carinatum deformity was corrected with limited incisions using an endoscopic approach.[15] They suggest that this approach is better indicated in preschool-aged children because of their skin quality and tone, as well because of the increased ease of costal dissection compared with adult patients.

In 2008, Fonkalsrud reported a series of 260 patients who underwent surgical correction of pectus carinatum deformities over a period of 37 years.[4] He concluded that, over time, the trend towards less extensive open techniques has resulted in “low morbidity, mild pain, short hospital stay and very good physiologic and cosmetic results.” His study included both pediatric and adult patients.

| Open surgical repair |

Various methods have been described. The reader is referred to Fonkalsrud (2008),[4] de Matos (1997),[17] Shamberger (1987),[18] Del Frari (2011),[19] and Cohee (2013) [20] for further details.

| Consultations |

Pectus carinatum has been associated with congenital heart disease. In these patients, and in those with suspected or identified cardiac pathology, preoperative cardiology evaluation is recommended.

Exercise testing may be performed in consultation with either a cardiologist or a pulmonologist.

Symptomatic patients with exertional dyspnea, tachypnea, or decreased endurance, as well as those with asthma symptoms, benefit from a pulmonology evaluation.

Individuals with pectus carinatum who have significant concerns about their body image or low self-esteem can benefit from psychological counseling.

| Activity |

Symptomatic patients may report decreased exercise tolerance and exertional dyspnea, which may limit activity. Fonkalsrud’s series (2008) reported improvement in exertional symptoms and endurance in all symptomatic patients within 3-6 months of surgical repair.[4]

Fonkalsrud’s recommendations for postoperative activity include the following: [4]

- Use incentive spirometer and encourage periodic deep breaths.

- Limit twisting movements of the chest for at least 4 months postoperatively.

- Avoid rapid elevation of the arms overhead for at least 4 months postoperatively.

- Encourage lower extremity exercise (may begin within first 2 wk after surgery).

- Light weights may be used to strengthen biceps and deltoids; the use of chest and abdominal muscles may be increased later (after 3-4 wk).

- Gym classes are not indicated for 5 months after surgery in school-aged children.

- Long-term recommendations include stretching exercises that involve pulling the shoulder

| Medication Summary |

Drug therapy currently is not a component of the standard of care in pectus carinatum. (See Treatment).

| Follow-up |

| Further Outpatient Care |

Long-term activity recommendations include stretching.

| Further Inpatient Care |

For information regarding these indications in pectus carinatum, (see Activity).

| Complications |

Complications vary according to treatment selection.

Ill-fitting braces can be associated with skin irritation and skin breakdown.

Shamberger reported a 3.9% complication rate with open surgical repair.[18] Complications include pneumothorax (2.6%), wound infection (0.7%), atelectasis (0.7%), and local tissue necrosis (0.7%). The mean postoperative stay was 5.8 days.

Fonkalsrud (2008) reported shorter hospital stays (mean, 2.6 d), mild postoperative pain, and low complication rate with limited resection and immediate chest stabilization.[4]

| Prognosis |

In prepubertal children with pectus carinatum who are compliant with bracing, success rates are excellent (up to 80%).

Excellent results (97.4%) have been reported by Fonkalsrud (2008) in patients who underwent surgical correction using a very limited resection of deformed cartilage and immediate chest stabilization.[4] In addition, he reported less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, lower complication rate, and decreased cost. Furthermore, he reported satisfactory cosmetic results with the less extensive repair, as well as a high rate of improvement in exertional symptoms compared with more extensive open surgical procedures.

Recurrences are rare.

Responses to quality-of-life questionnaires in patients who had undergone minimally invasive repair of their pectus deformity supported a positive impact on psychosocial function.[21]

| Patient Education |

Exertional symptoms may develop with pectus deformities and may not always be identified with standard pulmonary function testing.

| References |

- Coskun ZK, Turgut HB, Demirsoy S, Cansu A. The prevalence and effects of Pectus Excavatum and Pectus Carinatum on the respiratory function in children between 7-14 years old. Indian J Pediatr. 2010 Sep. 77(9):1017-9. [Medline]

- Steinmann C, Krille S, Mueller A, Weber P, Reingruber B, Martin A. Pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum patients suffer from lower quality of life and impaired body image: a control group comparison of psychological characteristics prior to surgical correction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011 Nov. 40(5):1138-45. [Medline]

- Derveaux L, Clarysse I, Ivanoff I, Demedts M. Preoperative and postoperative abnormalities in chest x-ray indices and in lung function in pectus deformities. Chest. 1989 Apr. 95(4):850-6. [Medline]

- Fonkalsrud EW. Surgical correction of pectus carinatum: lessons learned from 260 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2008 Jul. 43(7):1235-43. [Medline]

- Iakovlev VM, Nechaeva GI, Viktorova IA. [Clinical function of the myocardium and cardio- and hemodynamics in patients with pectus carinatum deformity]. Ter Arkh. 1990. 62(4):69-72. [Medline]

- Mielke CH, Winter RB. Pectus carinatum successfully treated with bracing. A case report. Int Orthop. 1993 Dec. 17(6):350-2. [Medline]

- Martinez-Ferro M, Fraire C, Bernard S. Dynamic compression system for the correction of pectus carinatum. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008 Aug. 17(3):194-200. [Medline]

- Obermeyer RJ, Goretsky MJ. Chest wall deformities in pediatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2012 Jun. 92(3):669-84, ix. [Medline]

- Calloway EH, Chhotani AN, Lee YZ, Phillips JD. Three-dimensional computed tomography for evaluation and management of children with complex chest wall anomalies: useful information or just pretty pictures?. J Pediatr Surg. 2011 Apr. 46(4):640-7. [Medline]

- Heithaus JL, Davenport S, Twyman KA, Torti EE, Batanian JR. An intragenic deletion of the gene MNAT1 in a family with pectus deformities. Am J Med Genet A. 2014 May. 164A (5):1293-7. [Medline]

- Castile RG, Staats BA, Westbrook PR. Symptomatic pectus deformities of the chest. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982 Sep. 126(3):564-8. [Medline]

- Frey AS, Garcia VF, Brown RL, et al. Nonoperative management of pectus carinatum. J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Jan. 41(1):40-5; discussion 40-5. [Medline]

- Lee RT, Moorman S, Schneider M, Sigalet DL. Bracing is an effective therapy for pectus carinatum: interim results. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Jan. 48(1):184-90. [Medline] [Braceworks]

- Wong KE, Gorton GE 3rd, Tashjian DB, Tirabassi MV, Moriarty KP. Evaluation of the treatment of pectus carinatum with compressive orthotic bracing using three dimensional body scans. J Pediatr Surg. 2014 Jun. 49 (6):924-7. [Medline]

- Kobayashi S, Yoza S, Komuro Y, Sakai Y, Ohmori K. Correction of pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum assisted by the endoscope. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Apr. 99(4):1037-45. [Medline]

- Wahba G, Nasr A, Bettolli M. A less intensive bracing protocol for pectus carinatum. J Pediatr Surg. 2017 Nov. 52 (11):1795-1799. [Medline]

- de Matos AC, Bernardo JE, Fernandes LE, Antunes MJ. Surgery of chest wall deformities. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997 Sep. 12(3):345-50. [Medline]

- Shamberger RC, Welch KJ. Surgical correction of pectus carinatum. J Pediatr Surg. 1987 Jan. 22(1):48-53. [Medline]

- Del Frari B, Schwabegger AH. Ten-year experience with the muscle split technique, bioabsorbable plates, and postoperative bracing for correction of pectus carinatum: the Innsbruck protocol. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011 Jun. 141(6):1403-9. [Medline]

- Cohee AS, Lin JR, Frantz FW, Kelly RE Jr. Staged management of pectus carinatum. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Feb. 48(2):315-20. [Medline]

- Bostanci K, Ozalper MH, Eldem B, Ozyurtkan MO, Issaka A, Ermerak NO. Quality of life of patients who have undergone the minimally invasive repair of pectus carinatum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013 Jan. 43(1):122-6. [Medline]

- Cano I, Anton-Pacheco JL, Garcia A, Rothenberg S. Video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy in infants. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006 Jun. 29(6):997-1000. [Medline]

- Fonkalsrud EW, DeUgarte D, Choi E. Repair of pectus excavatum and carinatum deformities in 116 adults. Ann Surg. 2002 Sep. 236(3):304-12; discussion 312-4. [Medline] [Full Text]

- Lacquet LK, Morshuis WJ, Folgering HT. Long-term results after correction of anterior chest wall deformities. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1998 Oct. 39(5):683-8. [Medline]

- O’Neill JA, Fonkalsrud EW, Coran AG, et al. Pediatric Surgery. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 1998.

- Sabiston D, ed. Textbook of Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1997.

- Westphal FL, Lima LC, Lima Neto JC, et al. Prevalence of pectus carinatum and pectus excavatum in students in the city of Manaus, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2009 Mar. 35(3):221-6. [Medline]

Source Medscape