Why are these scientists teaching seniors how to fall?

Rather than focus on avoiding tumbles, researchers at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute are using high-tech, hands-on trials to teach how to fall.

Cathrin Bradbury walks on sensor plates in the reactive balance training room at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, where scientists study how people correct their stride in response to a series of unpredictable and escalating jolts. COLE BURSTON PHOTOS FOR THE TORONTO STAR

By Cathrin Bradbury Contributing Columnist, Toronto Star March 24, 2023

I decided to make a pistachio cake for a fancy dinner. The pistachios, however, were out of reach on a top kitchen shelf. So I used a move I perfected 60 years ago in a snatch-and-grab operation for the cookie tin: hoist body; grab loot; hop to floor; run. The whole thing took five seconds, tops.

True, I hadn’t tried the move in a few years, and my arms were the first to object as they barely heaved me onto my stainless-steel kitchen counter. Which was unexpectedly slippery under my knees. I reached for the window to my right, thought better — glass, blood, death — grabbed the top shelf of the cupboard instead, which came off in my hand, but at least the bag of pistachios bounced to the floor, where I eventually got my bearings a couple minutes later, no harm done.

Two thoughts lingered, however: First, I should have made lemon squares. And second, maybe it was time to get wise about falling.

A scan of the latest research told me that one in three adults over 60, the three-quarter-life set set, will fall in a year, and two-thirds will fall again in the next six months, mainly because they neglected to talk to anyone about the first fall and so didn’t change the behaviour that caused it. That’s an expensive mistake: falls from older Canadians cost $5.6 billion in 2018 — 20 per cent of the total cost of injury in the country, according to Parachute, a Canadian charity focused on injury prevention.

Any aged person can and does fall — in fact, more than 50 per cent of young adults fall or trip in a typical year, according to a 2016 study of college undergraduates published in Human Movement Science. “Walking on two legs is a challenging task that is mechanically unstable, even for young, healthy adults,” said the report.

But after 60, the consequences can be catastrophic. Falls are the leading cause not just of injury, but of injury causing death, starting with the worst news. Nine out of 10 people who break their hip and four out of 10 adults who are admitted to a nursing home do so after a fall.

Scary numbers, and the response to that fear is often to become careful and self-limiting, which has its own risks of isolation and atrophy. PJ Paralysis, coined by a British RN, spawned the global movement, endpjparalysis.org. The big news, unfolding at the remarkable Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, is that it may be better to learn how to fall than to live in fear of falling. We’ll get to that soon.

But the place I began my education on falling — as most of us will — was with my family doctor.

“Please tell me you’re not standing on a kitchen chair to get things out of cupboards?” she asked.

“I am not,” I answered honestly, leaving out the botched pistachio caper as I sat across from her, smiling serenely.

A questionnaire, called the Balance Confidence scale, has people rate, among other things, their confidence standing tiptoe vs. standing on a chair to get at something out of reach. Most feel more secure on the kitchen chair. Beep! Incorrect. Worse, we think placing the back of the chair outward will protect us. Beep! You’ll fall up and over the high back, increasing the probability of breaking not just your arm but your neck, too.

Since most falls happen at home, I stopped at the dollar store on the way back from my GP for the supplies she’d suggested. I’d been meaning to safety-proof the house for my 11-month-old grandson, so it was a two-birds situation.

I bought a grabber for out-of-reach nuts. (Beep! used it once; too flimsy for a can of tomato paste, even; maybe follow my sister Laura’s lead and spend more than a dollar. She uses her superior grabber not just for reaching but weeding the garden and picking up socks.)

Nightlights, for bedrooms, hallways, stairs and nocturnal trips to the bathroom, the highest-risk zone in any home. More than 70 per cent of falls happen getting in and out of the tub, says the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Double-sided tape for that trippy bit of carpet.

The covers for the electrical outlets were for the baby, whose workaround was to pull out the bright nightlight and stick his finger in that socket.

Strength is a major prerequisite for a fall-free three-quarter life, and since my arms had struggled to raise me to the kitchen counter, my second stop was to Sarah Hamilton, a Toronto kinesiologist who’d helped me with a bad neck. Sarah would understand that at 68 my loss of arm strength was a given.

Beep! “I work with women in their 90s with grips of steel,” she said. “Strength has nothing to do with age.” I signed up for her online classes and now do strength exercises three times a week, most weeks. One month in, I successfully opened a bottle of wine on my own — cork, not screw top.

Confidence soaring, I upped the stakes and joined a falls prevention class at Toronto’s Baycrest Health Sciences. Nicole Campbell, the registered kinesiologist who runs the program, also waved off the age excuse.

“You can’t say, ‘I fell, but what do you expect? I am 90.” Beep! “Age alone is not a predictor of falls.” Having risk factors — a history of falls, lower-body weakness, visual and hearing issues, pain from arthritis, too much peeing (rushing to the danger zone) — is where training comes in.

At the Baycrest session I joined, part of a 10-week program, we practised multitasking while walking.

“One in three seniors say they were deep in thought or caught up in a strong feeling when they fell,” Campbell said as she asked the group of mostly 70s to walk fast and say the alphabet backwards. “Z, F, X, B.” I said my letters at random, because I can’t do the alphabet backwards even while standing still.

Reporter Cathrin Bradbury talks with senior scientist Avril Mansfield, right, and clinical research analyst David Jagroop at UHN’s fall lab. COLE BURSTON

Some of my fellow classmates, like me, were there to educate themselves before a fall happened; others had already had serious falls; most were spry, so I felt the competition was stiff. “The point of the exercise, when done properly” — Campbell paused, looking at me — “is to show how the brain will prioritize a cognitive task over a motor task. Let’s try again.

“You can see most falls coming,” said Campbell, directing me to a British Columbia study in long-term care between 2007 and 2010, where video cameras captured real-time falls.

The three activities associated with the highest proportion of falls covered the waterfront: forward walking; standing quietly (terrifyingly); and sitting down. The clinical finding was that most people had trouble weight shifting, and then were not able to make the corrective movements to recover, and you can see that in the videos, which are heart-wrenching to watch.

In one, a man catches and throws a beach ball several times. His quick-reflex arm response reminded me of my dad, who would have nailed the exercise even in his 90s. Except that when the game was over, perhaps distracted by his own prowess, the man tripped on his feet as he walked away. Whenever my siblings and I rushed to emergency after one of his many falls in the last years of his life, my father would say, “Tripped on my own two feet, I guess.”

Which brings me to Dr. Mark Bayley, medical program director at the Toronto Rehabilitation Insititute. Bayley has a goal that radically departs from the idea of fall prevention. Namely, that every at-risk Canadian, like my dad once was, learns how to fall — instead of how not to fall — as a routine part of medical practice.

“We think of a fall as losing your balance.” It’s a snowy March morning in our high-hazard Toronto winter as I talk on the phone with Bayley. Except that walking, as the experts have agreed, is about constantly losing your balance as you shift your weight from one foot to the other.

“What happens in a fall, on the other hand, is that something perturbs your balance” — maybe ice, maybe uneven pavement. “The fall is a failure of perturbation.” Right now, Bayley said, we’re focused on trying not to fall when we need to be focused on how to better recover when something causes us to fall.

“So, the question came up, could we teach people how to fall? Could you push them and watch how their balance works and use that to analyze how they respond to moments of imbalance?”

Two days later, in Toronto Rehab’s Reactive Balance Training room, I was strapped into a harness, walked out to a high platform, and hooked onto a cable dangling from the ceiling. “THREE, TWO, ONE, GO,” said David Jagroop, a clinical research analyst with the program. I walked briskly, forewarned that the ground would shift frontwards, backwards, and side to side, in a series of unpredictable and escalating jolts.

“Normally,” explained senior scientist Avril Mansfield, who sat behind a two-way mirror operating the controls, “people would be hooked to motion-capture markers and electrodes, and we’d have a complete analysis.”

Hundreds of patients have done exactly that, with a remarkable 40 per cent success rate in preventing future falls. “But just watching you,” Mansfield said, “I can see you have a tendency to overcorrect when stumbling frontwards or backwards.”

The ideal is one wide corrective step instead of several small ones, when falls are more likely to occur. “You did well when perturbed sideways,” she said encouragingly, then mentioned the subway stance, “with one foot in front of the other to balance you front to back.” Except that I use a wide gait on the subway as well, which is perhaps why I correct “sideways even when falling forward.”

I asked Mansfield what she thought of the judo studios in Quebec and the Netherlands offering classes to the elderly on how to tumble and roll. She stared at me silently, opening her eyes slightly wider. I’m taking that as a Beep!

But judo classes do have an accessibility that Toronto Rehab is already addressing. “It’s not practical to test everyone in a high-tech environment where the costs” — $2 million for the facility alone — “are prohibitive,” Mansfield said. The hospital has moved much of the training to the therapeutic, with the idea that falling in a controlled and safe environment should be part of a patient’s recovery plan.

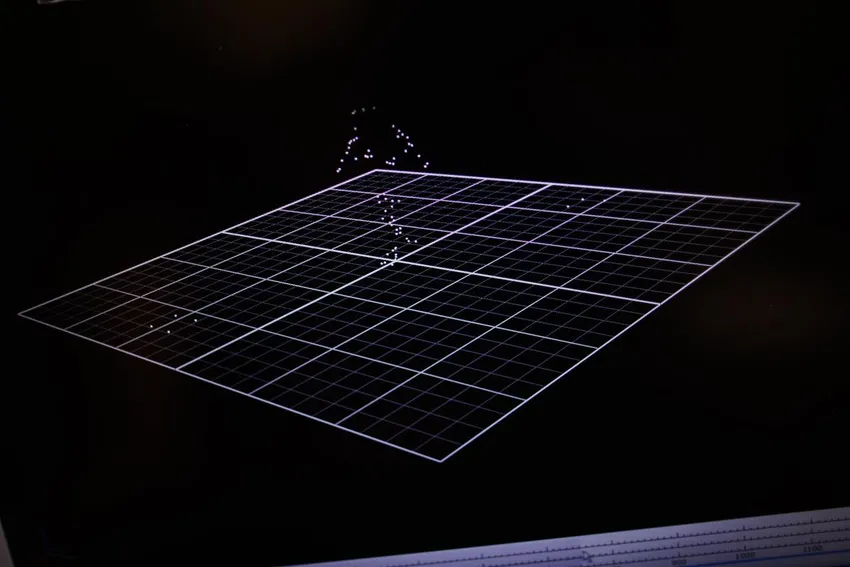

An animated diagram shows a subject walking on sensors at the UHN lab. COLE BURSTON

“A zero-falls recovery policy is unattainable,” said Angie Andreoli, a physiotherapist in the brain injury department of Toronto Rehab. We’re talking just outside the department’s gym, where patients are being put through their paces.

“Our goal in therapy is to fall and then learn from it.” If the fall takes place in the safety of the hospital, with the patient is practising activities they’ll have to perform when they get home, “the benefits outweigh the risk.”

Before you get to being jerked or pushed in a high- or low-tech environment, however, there’s a simple 10-second balance test that Bayley would like Canadians over 75 to perform for their family doctor. The test predicts how long you’ll live, “whether you have any other medical issues whatsoever.”

As explained in the 2022 British Journal of Sports Medicine report, people over 50 years old who were unable to stand on one foot for 10 seconds were nearly twice as likely to die in the next 10 years — not only of falling, but of any cause. Of the 1,700 adults in the study, 20 per cent didn’t pass the test.

“Jesus,” I said to Bayley as I secretly balanced on one foot and then the other while we continued our phone conversation.

After our call, I went a long way down that rabbit hole, watching dozens of people of all ages filming themselves passing the test before I came upon a previous 2016 study from the same group. This one found that the ability to sit on the floor and then stand up without using your hands for support could predict your risk of death in the next six years. Are you kidding me?

I started this article asking how to fall, and so not become disabled at this risky age, and ended up trying to figure out how soon I’ll die. To that question, there is no answer. Beep!

| Cathrin Bradbury is a Toronto-based journalist and freelance contributor for the Star. Follow her on Twitter @CathrinBradbury. Email mcbradbury@gmail.com |

Source Toronto Star

| References |

Video capture of the circumstances of falls in elderly people residing in long-term care: an observational study, Robinovitch SN, Feldman F, Yang Y, Schonnop R, Leung PM, Sarraf T, Sims-Gould J, Loughin M. Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381(9860):47-54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61263-X. Epub 2012 Oct 17. Erratum in: Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381(9860):28. Full text, PDF

Successful 10-second one-legged stance performance predicts survival in middle-aged and older individuals, Araujo CG, de Souza E Silva CG, Laukkanen JA, Fiatarone Singh M, Kunutsor SK, Myers J, Franca JF, Castro CL. Br J Sports Med. 2022 Sep;56(17):975-980. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105360. Epub 2022 Jun 21. Full text

Falls in young adults: Perceived causes and environmental factors assessed with a daily online survey, Heijnen MJ, Rietdyk S. Hum Mov Sci. 2016 Apr;46:86-95. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2015.12.007. Epub 2015 Dec 29.

The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale, Powell LE, Myers AM. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995 Jan;50A(1):M28-34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28.

| Further reading |

Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (ABC Scale), Annabel Wildschut Author, Annie Rochette Editor, Johanne Filiatrault, erg., Ph.D. Expert Reviewer, Gabriel Plumier, Content consistency. Stroke Engine. Evidence Reviewed as of before: 30-11-2020.

Reliability and validity of the German short version of the Activities specific Balance Confidence (ABC-D6) scale in older adults, Schott N. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014 Sep-Oct;59(2):272-9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.05.003. Epub 2014 Jun 4.

Comparison of three established measures of fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: psychometric testing, Huang TT, Wang WS. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Oct;46(10):1313-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.010. Epub 2009 Apr 24.

Evidence of the psychometric qualities of a simplified version of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale for community-dwelling seniors, Filiatrault J, Gauvin L, Fournier M, Parisien M, Robitaille Y, Laforest S, Corriveau H, Richard L. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 May;88(5):664-72. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.003.

Also see

‘PJ paralysis’: Why advocates are pushing to get patients out of pyjamas CTV