Corrective chest surgery changed my life

Pectus excavatum surgery was the most painful experience of my life, but the self-confidence I gained made it worth it.

Playing in the surf. Porto Covo, Portugal. Wikimedia Commons

Tears rushed down my face as I looked at my newly-rebuilt chest. At first I didn’t even grasp what I was looking at because it appeared so foreign to me. Through the shock and the tears I asked, “Whose body am I in exactly?”

By Clayton Goodwin, The Calgary Journal 14 October 2011

At age 10, I had just gone through an incredibly painful and intense surgery that most people will never experience. I knew I would never be the same again.

I was born with a severely-deformed chest. Generally speaking the average person’s ribcage is shaped straight across, and the chest is relatively flat.

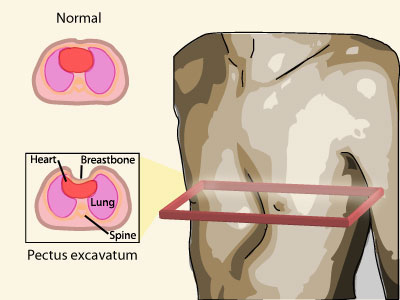

My ribcage had a predominant curve to it and my sternum dipped inwards towards my spine. It looked as though I had a dent right in the middle of my chest. Another way to think of it is as if someone had punched me where my ribs meet in the middle and permanently bent all the ribs inwards.

According to what physicians had told me, one in every 300 children in the world is born with pectus excavatum. But it varies in severity from person to person, which means that some people will have a more significant curve in their chest than others.

My chest was as severe as it gets.

I was informed by my surgeon that the deformity is passed through male genes and it always skips a generation. My father doesn’t have it, but my grandfather has a very slight form of it. His abnormality is almost non-existent; therefore it didn’t require any surgery.

I can say with confidence that my chest was a pretty grotesque sight. As a result, there were a number of times I had to endure teasing and bullying from other kids. For years I hid my chest from everyone. I would even swim with a shirt on because I was so self-conscious of the way I looked.

My parents tried their best to comfort me and help me through the difficult stages of bullying. They tried to reassure me, “Your chest looks like this now, but as you grow your muscles will grow too, and change the way you look.”

It helped to hear that. But deep down I knew that my chest wasn’t going to change by itself.

The turning point in my self-confidence came when I reached the higher levels of swimming classes when I was eight. I had started to be made fun of for wearing a shirt in the pool, and realizing I was going to be made fun of no matter what, I finally took the shirt off and bared my deformity for all to see. I had to deal with some more teasing and gawking from other kids, but those experiences forced me to learn how to laugh things off, which I think is an important defence mechanism when faced with the immaturity of others.

Until the age of 10, I always noticed how tired I would get during any physical activity. It was always difficult to breath. I already had asthma, but I could tell this was different, and my parents recognized it as well.

After speaking with both our family doctor, and my pediatrician, my family and I learned that my caved-in chest was compressing both my lungs and was pushing my heart over to the far left side of my body. My deformed chest was turning out to be very detrimental to both my day-to-day life, and my overall physical growth. We decided to look into the option of elective surgery.

Over the next few months I had to sit through countless appointments with what seemed like every kind of specialist on the planet. For a 10-year-old kid, it was a lot to handle. None of my friends had to constantly leave class to go the Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary. I was insanely jealous of all the “normal” kids at my school. But I just bit-the-bullet and dealt with it all the best I could, mainly by remembering that I would eventually be like everyone else — or at least look like everyone else.

Eventually, my family and I met with Dr. David Sigalet, a pediatric surgeon, during one of our many visits to the hospital. He proposed a relatively new surgery — which at the time had only been around for 10 years — and it seemed like the best option. Although I was absolutely terrified, I agreed to the pectus excavatum surgery.

After I made my decision, I knew that I had a long and painful road ahead of me, but the magnitude of the situation didn’t really sink in at the time. I had just begun a two-year process that would change my life forever.

| Preparing for the surgery |

The first step was to go through all the preliminary tests leading up to the surgery. First of all, the doctors wanted a sense of my fitness so they could gauge how much the surgery would benefit me. There were multiple breathing tests where I had to sit in a locked chamber and breathe into a tube in order to measure my lung capacity at rest.

My favourite test was the VO2 Max test, which measured my lung capacity. First, the physicians hooked me up with all sorts of wires and electrodes. They then put this headgear on me that had a tube in front of my mouth for breathing. At that point I was instructed to ride the stationary bike as hard as I could for as long as I could until I felt like passing out. Some people may think I am odd for liking such a test, but I found it interesting because it measured exactly what my physical limits were.

And I wanted to do the best I could so I would have an accurate reading of how my body would change after my operation.

Lastly, I had to go through a number of different blood tests. I wasn’t too thrilled of having so many needles put in me, but I knew it had to be done. The worst thing about it was when I was told I would have to give extra blood so the surgeon would have some back up blood in case anything goes wrong during the operation. That wasn’t exactly the most encouraging thing for me to hear before getting sliced open.

Now that the preliminary tests were complete, I had about a month to wait until my surgery date. At this point, I was nearing the end of Grade 6. It was an extremely nerve-wracking month, which wasn’t made any easier by the fact that I had to complete provincial exams. I made it through that month, and my surgery was scheduled for the beginning of July so I could recuperate during the summer and be able to attend junior high that following September.

| A cross-section of a chest impacted by pectus excavatum. My sternum dipped in towards my spine, compressing my lungs and pushing my heart to the far left side of my chest. Illustration by Derek Mange. |

| The Nuss procedure |

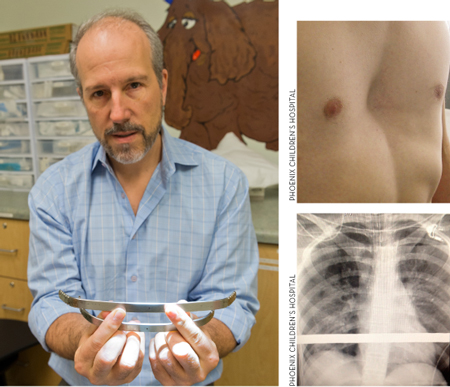

The operation itself is called “pectus excavatum surgery.” There are two different ways of doing it – the Ravitch procedure and the Nuss procedure. The Ravitch procedure is done by cutting open the front of the chest and then cutting the rib cartilage on both sides of the rib cage.

The sternum is then flattened, and one or more bars are inserted so the sternum keeps its new shape. This option leaves the patient with gruesome scars all over their chest, which was why I did not choose it. I went with the Nuss procedure which is minimally invasive, and only left me with two scars. I have a scar on both sides of my chest, and each scar is about six centimetres in length. They are both located just below my armpits.

| The Nuss procedure. David Notrica MD, left, holds the corrective pectus brace implant. Top right: Pre-surgery male patient with pectus excavatum. Bottom right: Tatum’s post-surgery chest X-ray. The white line shows the brace in place. Raising Arizona Kids |

The Nuss surgery was performed by cutting into both of my sides and then the surgeon made a pathway through my chest using a camera and various other instruments. After the path was made, a titanium bar was slid horizontally through my chest.

The bar was specially made for me, and was curved to fit the shape of a normal looking chest. When it was first put through the path in my chest, the doctors put it in upside down.

At that point it made a U-shape and the two ends were pointing up and it was still visible outside through the cuts on my body. The doctors then flipped the bar, pushing my indented chest outwards and forcing it to take the shape of the bar. The surgeons finished the procedure by wrapping the ends of the bar around my muscle fibre and added an extra stabilizer bar about the size of a small pocket knife to my left side.

I was then sewn up and sent to the recovery room.

| After the procedure |

I woke up in a daze.

Everything was blurry and all I could see were bright lights and shadows moving around me. Nurses noticed I was awake and came over to see how I was doing. They gave me an orange Popsicle to choke down. Right before I was rolled out of the mass recovery room to a smaller one, I remember thinking, “Hey, I’m not in any pain; this might actually be pretty easy.”

Little did I know that the drugs were about to fade, and I was just starting an excruciating week.

Once I was able to easily move my head, the first thing I did was look down at my chest. My immediate family was there and we all cried in unison at the astonishing sight of my reconstructed chest.

After we regained some composure I started to take in exactly where I was. There were tubes coming out of my arms and my neck to administer drugs. I had two tubes coming out of my chest for excess fluid drainage. Family and friends had brought stuffed animals and movies for me, all sitting on a table at the end of my bed.

The first couple of nights at the hospital consisted of constant checkups from nurses and doctors to see how I was doing. As a 10-year-old kid, I was scared for those first couple nights, so my dad slept beside me in what looked to be an uncomfortable wooden chair.

How did I feel after the surgery?

Well, think of the worst physical pain you have ever felt. Now multiply that by 100. My entire body hurt, which I didn’t understand seeing as how I had surgery on my chest, not my legs. Now that I look back, it is obvious why I was in so much pain. I just had all my ribs bent upwards. It is not like I bumped my elbow. My chest had just been reconstructed, so pain radiated throughout my body. The nurses kept pumping morphine into me to help with the pain. It was great, until it wore off.

Every afternoon I had a physiotherapist come in and make me walk the halls to regain my strength. I am not usually an angry person. But I hated that physiotherapist and anyone else that made me get up from bed. I swore and told everyone off using a string of profanities.

On top of the physical pain, I was unable to eat anything. I couldn’t keep anything down. Hospital food is gross to begin with, but it all tasted worse than normal. My mom even brought in toast with Cheez Whiz, which is one of my favourite things to eat, but I couldn’t stand to look at it.

Anytime I managed to eat something, it stayed down for about an hour if I was lucky. I was throwing up that entire week. I eventually had to ask for a huge cooking bowl to vomit into, because the hospital would usually just give me small paper trays that are good for holding French fries, but not so good for holding all my “returned” food. I lost count how many times I threw up on myself during that week.

Between that, the pain, and the constant swearing, I imagine the nurses must have just been delighted every time they had to go to my room.

Near the end of the week at the hospital, I had some friends and extended family come and visit. They never stayed for long. I figure they were rather turned off at the sight of a vomiting, tube-laden kid with the mouth of a trucker.

At this point, I didn’t think things could get much worse.

And then other kids started to use the bed beside me.

The worst roommate was a seven-year-old child who had been attacked by a dog. By that time I was used to being alone in that room and I didn’t want to deal with other people. I did my fair share of moaning and crying, but I didn’t want to listen to others in pain — this was my time to suffer.

At night that stupid kid on the other side of the curtain wouldn’t stop complaining. I would constantly yell at him, “Shut the f— up!”

In retrospect, I was kind of a jerk, and I was lucky his parents weren’t staying the night. But I was in so much pain that I felt justified in my yelling.

Finally, I was able to leave the vomit-covered, pain-inducing hell that was the hospital. For the most part, that summer consisted of sleeping, watching TV, and more sleeping. I know that sounds pretty good, but my pain only subsided enough so I could go home. I was constantly hurting for the next two months.

My physiotherapist was replaced by my grandmother who made me walk around the block for strength. (I didn’t swear at her, in case you’re wondering.) Instead of hospital tubes, I had to wear a specially-made brace that helped form my chest. I hated that brace. It was made of two curved metal bars and rubber pads that put pressure on certain areas of my chest. It was completed with two ski-boot locks, one on both sides.

The thing limited my mobility, and I also had to sleep in it. Sleeping on metal bars is not exactly easy to do. So now I had a bar inside of me, and two more bars on the outside. I was beginning to feel more like a robot than a kid about to go into junior high.

| Back to life |

Going into junior high was basically normal for me; the only real difference is that I couldn’t participate in gym classes, which sucked. It still hurt to physically exert myself, and I couldn’t risk getting hit in the chest with anything. I felt kind of like a china doll. So my Grade 7 gym class consisted of reading in the library.

It was as boring as it sounds. To get through it I kept telling myself, “This blows, but at I am no longer a deformed freak.”

Over the next year I had numerous visits with more specialists at the hospital. I went through all of the post-surgery tests and my scores were astronomically higher than before. I was then starting to feel stronger and emotionally better about myself. It was then that I began to realize I made the right choice, and the operation was worth it.

On the second year anniversary of my surgery I had to go back under the knife one last time. The doctors could not just leave the bar inside of me because it would eventually start to limit my growth if they did, so it had to come out.

Over the painful last two years, my chest solidified into its normal shape, which is why the bar was no longer needed. I was cut open and the bar was removed. My stay at the hospital was only one day, and I fully recovered within a few weeks. I was finally done.

| A new beginning |

The operation was the most painful experience of my life. I wouldn’t wish that kind of pain on my worst enemy. But as I look back at everything I went through, and who I am now, I know that it was all worth it.

My surgery opened up an infinite amount of doors for me for the rest of my life, and gave me the physical ability to do whatever I want.

The operation not only freed me physically, but emotionally as well. Since my surgery, I have had absolutely no reservations about showing my chest in public. In fact I actually relish in telling people what I went through because they are always astonished by my story. Even though the entire ordeal was extremely difficult, it gave me a sense of self-confidence that before the operation I never thought I would have. I don’t regret anything that happened, because in the end the benefits greatly outweighed the costs.

![]() Source The Calgary Journal

Source The Calgary Journal

Also see

☞ Bracing results in significant improvements in pectus carinatum

Pediatric Surgery Clinic Alberta Children’s Hospital

Pectus excavatum – A simpler surgery to fix “sunken chest” Raising Arizona Kids

What is Pectus Excavatum? fixpectus.com

Pectus Excavatum Surgery London Health Sciences Centre LHSC